Atlanta’s art scene is experiencing an unprecedented period of growth, with a class of collectors finding their voice (and tight-knit community).

Some patrons are looking toward contemporary Black abstraction, others toward historic landscapes or overlooked figures with urgent practices. Across the board, collections double as living archives—personal, political, and always in dialogue with the Georgia city’s shifting cultural landscape.

As the Atlanta Art Fair returns for its second edition, CULTURED sat down with a cross-section of the city’s collectors to explore how their walls reflect Atlanta itself—restless, layered, and always rewriting the narrative of what Southern art can be.

Esohe and George Galbreath

Esohe and George Galbreath have each forged their own paths in the arts, from George’s ongoing tenure as a teacher and the founder of Westlake High School’s fine arts program, to Esohe’s boutique art consulting business, Sohé Solutions, which advises clients on best practices in collecting, curating, arts education, and financial consulting. Their annual art party, ARTiculate ATL, features a selection of local artists and offers a new platform for their work.

How would you characterize the Atlanta art scene?

Esohe: Vibrant. Atlanta has been experiencing a kind of renaissance for the last 20 to 30 years, starting slightly before the 1996 Olympics. We often hear stories of artists moving here in the mid-’90s who continue to leave their mark on the city and inspire new generations.

George: Like the South itself, Atlanta’s art scene moves at its own pace. It allows time for artists and communities to develop. Even though the scene is thriving, it’s still young in terms of infrastructure.

Esohe: That means there’s still space for new people, new ideas, and new programming. For us, that openness made it easier to find our place here, and it continues to create opportunities for what comes next.

Can you describe your collection for us?

Esohe: It’s fun, eclectic, and large; about 200 works collected over the past 12–13 years. Our collection is very much a time capsule of this moment in Atlanta, focused primarily on emerging artists. Taken together, the works provide a snapshot of the city’s renaissance and the creativity defining this era.

If you could instantly snap your fingers and own the art collection of anyone, who would it be and why?

Esohe: Honestly, no one. Our collection is deeply personal, built on relationships, friendships, and shared experiences. That can’t really be replaced by anyone else’s collection.

George: That said, there are two artists tied to Atlanta whose works we’d love to add: Radcliffe Bailey and Kara Walker. We’ve admired their work in other collections and hope to bring them into ours one day.

What factors do you consider when growing your collection, and how has it changed alongside your home?

George: As we’ve evolved as collectors, so have our tastes. Early on, we were drawn to the human figure, especially in response to cultural moments, like the murder of George Floyd. We were drawn to work that engaged the Black figure and body.

Esohe: Practically speaking, our considerations have shifted too. At first, size wasn’t a concern, but now, with nearly 200 pieces, it’s something we think about carefully. We’ve started intentionally seeking smaller works so we can continue to diversify the artists and voices represented in our collection.

What is the strangest negotiation you ever had as an artist or dealer?

George: One that stands out was with Paper Frank. We found ourselves in East Atlanta after 10 p.m. for a one-night-only studio sale. His studio was up a dark fire escape in an alleyway, which felt a little intimidating at first. But once inside, we saw a young boy with his mother buying one of his first pieces. The joy and excitement of that moment completely shifted the energy. What began as a nerve-racking experience turned into one of our most memorable art encounters.

What book changed the way you think about art?

George: Several books from my time at Howard University still shape how we think about art and collecting, particularly within the African American community. One such book is African-American Art by Sharon E. Patton. However, the most influential has been The Galbreath Collection: A Decade of Collecting Atlanta. Creating that book was an act of love, and it gave us the perspective to recognize ourselves as stewards as well as collectors.

Esohe: Another influence came from writings on the salons and home exhibitions hosted by African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. That history inspired us to think about the intentionality behind how we collect, host, and share art in our home. The idea that our gatherings could both introduce artists to new audiences and serve as inspiration to others continues to guide how we live with our collection.

Everett Long

Everett Long’s strategy and consulting firm has nurtured the development of executive leadership programs and organizational strategy across industries. With his husband Fred, the couple have collected art across price points, global locales, and points of sentimentality (including a specially-commissioned painting that turned into a proposal gift in lieu of a ring).

How would you characterize the personality of the Atlanta art scene?

Independent, open, and close-knit. The artists here really have their own unique, independent styles that draw from their experiences, whether they’re from Atlanta or not. I find people to be really engaged. As an emerging collector, I’ve really found fellow collectors at all levels to be really open to giving up their time, advice and of course, sharing their collections.

Can you describe your collection for us?

I collect with my husband, Fred. We collect contemporary art, which Fred has taken to describing them of identity, memory, and resilience. We have about 65 pieces with a good balance of figurative and abstract work– lately I’ve been obsessed with contemporary Black abstractionists. (My friend and artist Jamele Wright Sr. has taught me a lot). The collection features many Atlanta and Southern artists, but lately we have been branching out to the national scene as well around the globe. Our most recent purchases were a work on paper by Michi Meko, a set of Ayanna Jackson photos, and a huge Radcliffe Bailey print from his residence at Sam Fox.

If you could snap your fingers and instantly own the art collection of anyone else, who would it be and why?

Kent Kelley. He has a bold and beautiful collection of contemporary Black art that spans the best of the best national artists, while also maintaining a balance of Atlanta artists.

What factors do you consider when expanding your collection? And how has your collection changed alongside your home?

When expanding our collection, gut reaction and feeling means a lot. The piece has to evoke curiosity and a desire to go deeper and learn more. We are both highly academic and so I love to do the research, talk to others, and build a case for the purchase. The artist’s story about the piece and their practice is also really important. We like to make a decision over time and spend time with the artist and pieces that intrigue us. A favorite moment was spending an afternoon in the back of Johnson Lowe Gallery with art we were honing in on strewn around us. About an hour in, the artist, Sergio Suarez, showed up and took us on his personal journey with the art for another hour–we definitely left with a bigger piece than what we had planned!

Which work in your home provokes the most conversation from visitors?

The piece that provokes the most conversation is by Victoria Dugger, called The Devil Makes Three. The painting is on a bright yellow background and has two striking, black demon-looking figures. There is a lot of mixed media and sculptural elements as well, so you want to touch it. Of course, it has Dugger’s Southern Gothic style, which means it’s girly and creepy. It’s hung in a space where, when people enter our main room, they can see the painting in the next room, and they’re drawn to walk towards it.

What book changed the way you think about art?

The exhibition book from the Met’s “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” show was the first exhibition guide that I read from cover to cover. After that, I changed the way I think about art, because I changed the way I learn about art. I started going deeper. When I saw the show for the second time I enjoyed it exponentially more. Now, I always have an exhibition book that I’m reading and eventually finish from cover to cover. Right now, I’m almost done with Rashid Johnson’s “A Poem For Deep Thinkers.”

Hassan Smith

As the founder of investment entity Ellaby Holdings and longtime advisor to John Legend, Smith developed a cultural fluency grounded in music alongside his art collecting. Smith focuses on collecting art of the African diaspora, steering his time and resources toward elevating this class of artists in Atlanta.

How would you characterize the personality of the Atlanta art scene?

Atlanta’s art scene carries its history, spirituality, and storytelling with an undeniable pride, yet it also reaches outward, engaging in global dialogues across contemporary art, fashion, film, and music. Rather than being insular or elitist, Atlanta’s art spaces often emphasize accessibility and collaboration. Grassroots collectives, artist-run spaces like The Goat Farm, and community festivals are just as influential as major institutions like the High Museum. The city’s legacy as the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement deeply informs its creative expressions. Many Atlanta artists explore themes of identity, race, and memory, making their work feel alive, urgent, and socially aware.

Can you describe your collection for us?

Over the past 15 years of collecting, we have amassed over 300 works of art in various mediums. Our collection includes photography by Gordon Parks and Rashid Johnson; sculptures by Donald Locke; and paintings by legacy artists like Buford Delaney, Frank Bowling, David Driskell, Ben Enwonwu, Betye Saar, Jack Whitten, and Norman Lewis. We also collect contemporary painters like Patrick Eugène, Deborah Roberts, Esther Mahlangu, Alteronce Gumby, Rick Lowe, and Stanley Whitney. Additionally, the collection features important prints and monotypes by Romare Bearden and Faith Ringgold.

If you could snap your fingers and instantly own the art collection of anyone else, who would it be and why?

Honestly, I wouldn’t want anyone’s collection but the one we’ve cultivated at the Hassan K. Smith Collection. Of course, I admire other people’s collections, but there is nothing like hand-picking every work of art to tell your own unique story. It’s important that our children understand the love, care, and time spent learning—and the cultivation of stories—that will stay with us for generations. Our robust collection is definitely one of my proudest achievements. That being said, I do deeply admire the collections of Marty & Anita Nesbitt, Pamela Joyner, Kent Kelly, and Elliot Perry.

What factors do you consider when expanding your collection? And how has your collection changed alongside your home?

I consider many factors when expanding the collection—among them the transfer of knowledge within community, viewing as much work as possible, and reading and studying to gain a better perspective on structure and method. Our collection has evolved over the years as we’ve learned and refined our tastes and interests. I tend to collect works from various eras; at the moment, I’ve been especially interested in acquiring pieces from legacy artists alongside emerging contemporary voices. It’s a feeling that is indescribable, to see where emerging and mid-career artists draw inspiration from—you can often trace the lineage of influence from one artist to another.

Which work in your home provokes the most conversation from visitors?

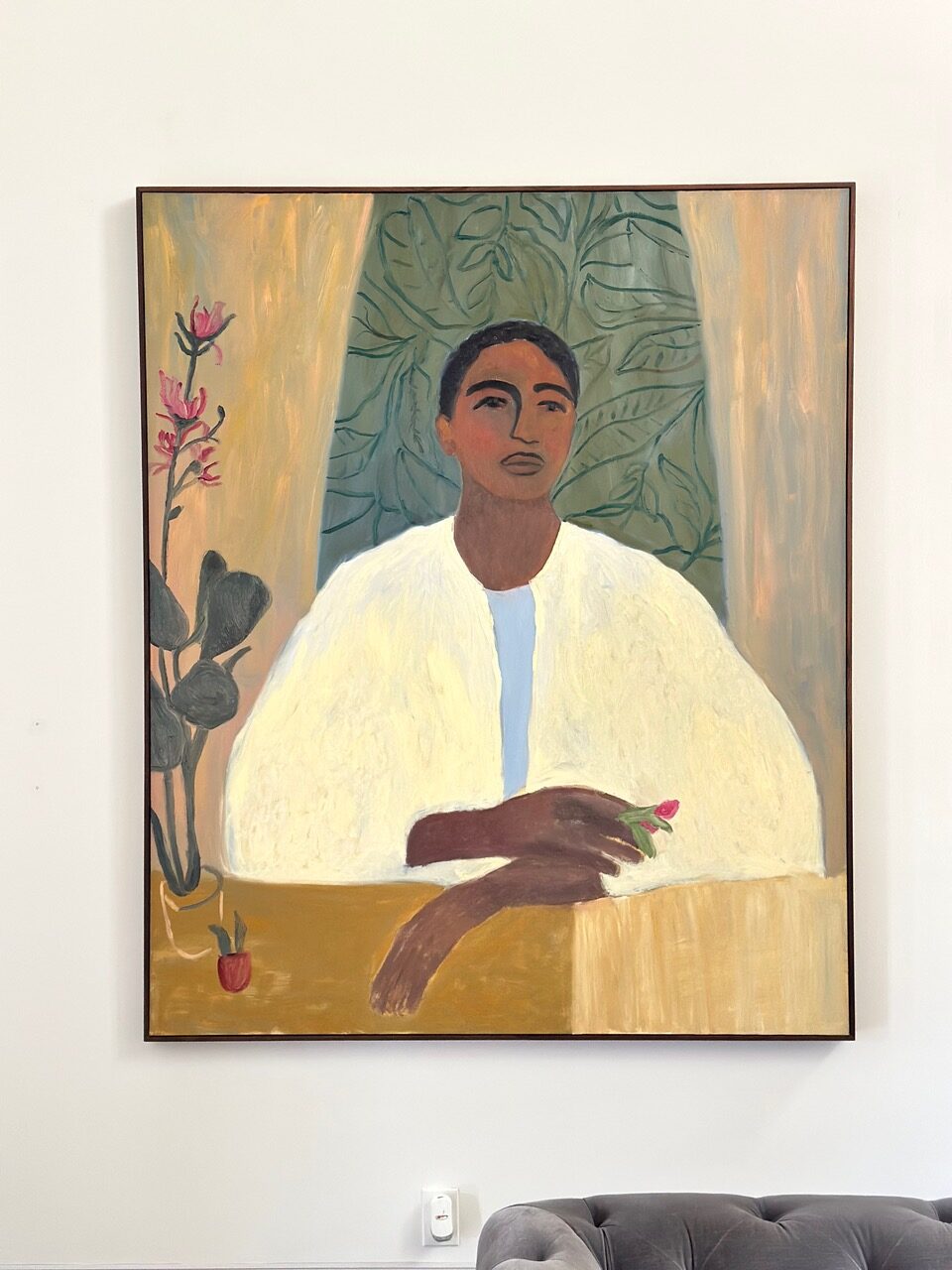

I would have to say our Patrick Eugène work, The Room Remembers. It’s a beautiful, large-scale oil on canvas, museum-quality, measuring 132″ x 84″. He wrote, “This painting is a meditation on community, memory, and the quiet power of gathering. I wanted to capture a moment that feels both specific and universal—a room full of Black figures, not posed but present, suspended in the intimacy of shared time. The figures are intentionally simplified, their features softened to invite a collective reading rather than individual identity. In this way, the painting becomes a kind of archive of family dinners, church suppers, neighborhood meetings—spaces that have long functioned as sites of survival, strategy, and spiritual renewal in Black life.”

Do you have an art fair or museum-going uniform?

I typically wear very comfortable white New Balance running shoes, black Prada joggers, and either a black or gray Balmain crewneck sweatshirt. I keep it simple, so I can enjoy the experience. Sit when I want to, stand when I need to. Just taking it all in.

Robert Balentine

Robert Balentine is the founder of Balentine—a wealth management firm which partners with high-net-worth families and entrepreneurs on preserving and propelling their assets. Balentine and his family created the Southern Highlands Reserve in North Carolina—a 120-acre nature reserve—and are involved with the Garden Conservancy, the Southeastern Horticultural Society, and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra.

How would you characterize the personality of the Atlanta art scene?

Atlanta’s art scene is dynamic, diverse, and deeply tied to the city’s identity as a crossroads of Southern tradition, Black culture, and modern global influences. It mixes established institutions with grassroots creativity, giving it both depth and constant renewal. My son is an artist and art educator, so I experience it through his eyes, and through our involvement with the Atlanta Art Fair, now in its second year. The Balentine Prize is specifically meant to recognize an emerging artist, which is very exciting.

Can you describe your collection for us?

Most of the paintings Betty and I have collected are American works, mostly from the Hudson River Valley school. They tend to be pastoral and nature-themed, reflecting our love of landscapes and gardens. This makes sense if you’re familiar with Southern Highlands Reserve, the native plant arboretum in Western North Carolina we founded more than two decades ago. They’re now doing important conservation work and their gardens are a view that I’ll never tire of. Among the pieces in our collection of which I’m most fond of are works by Albert Bierstadt, Charles Courtney Curran, Levi Wells Prentice, Edmund Darch Lewis, and Edwin Moran.

What factors do you consider when expanding your collection? And how has your collection changed alongside your home?

When we add to the collection, we’re looking first for a personal connection—does the subject matter speak to us? That’s why so much of what we own features pastoral or nature themes. I also look for quality and provenance. Over time, our collection has evolved with the spaces we’ve lived in. Larger, more monumental works now hang in our North Carolina home, where they feel at scale with the architecture, while smaller and more intimate pieces are in Atlanta. And of course, it’s changed in another meaningful way: my son is a professional artist, and we proudly hang several of his works in our office. Having his art alongside these 19th-century American painters gives the collection a more personal, multi-generational dimension.

What is the strangest negotiation you’ve ever had with an artist or dealer?

I once bought a painting on auction at Christie’s, only to later discover that the frame was borrowed and wasn’t included, with no acknowledgement otherwise. It all worked out fine, but only in the art world can you buy the painting and still have to haggle over the frame.

What book changed the way you think about art?

I’m reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo da Vinci, and finding myself fascinated by the way da Vinci blended mathematics and art—the Fibonacci sequence, the golden mean—to create beauty rooted in structure. As someone who has spent a career in investing, that marriage of numbers and creativity really resonates with me.

in your life?

in your life?