The girls roast pigs, comb each other’s hair, hang boys by their feet, bath in the stream. They hunt and kiss and band together into large troops that could bring the world down.

These are all scenes from Justine Kurland‘s “Girl Pictures.” The artist starting making the 1997-2002 series to stage images of youthful defiance over the course of long road trips. What she made, while zigzagging across America, were photographs that captured the sense of communion young women feel when they are given the space to make belief with one another. Reflecting on this seminal body of work, Kurland wrote, “I intended for them to play act a state of communal bliss. As it turned out, the girls didn’t have to pretend.”

On a Monday morning in July, Kurland once again opened the portal to her radical female imaginary, this time for fashion designer Colleen Allen, who—shot alongside a handful of like-minded friends and muses, including legendary executive Judy Collinson, jeweler Alice Waese, and models Charlotte O’Donell and Irina Shnitman—stepped through the looking glass in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

It was a dream come true for Allen, 29, who has seen herself time and again in Kurland’s images of teenager stripped down to their realness. The photographs remain a touchstone for her namesake line which, in the past year or so, has amassed a substantial girl gang all on its own. What Allen’s clothes share with Kurland’s “Girl Pictures” is an otherworldliness—a vision of girlhood unhooked from The Wing-like commodification of gender and instead infused with a deep reverence for art history and the contributions of women whose convictions once rendered them hysterical, ostractized, or worse.

Muses for past seasons have included witches real and imagined, including Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning. For her upcoming spring collection, Allen found her spark in something slightly more contemporary: Red Comet, Heather Clark’s recent biography of Sylvia Plath. Listening to the audiobook in her studio, Allen was struck by parallels to her own life: For one thing, both American women crossed the Atlantic for their education. Allen was particularly intrigued to learn that Plath had once been a fashion intern in New York—and loathed it.

She fixated on an anecdote in which Plath and her fellow interns defiantly tossed their mandatory girdles off a rooftop, an episode that made its way, in an altered form, into Plath’s best-known work, The Bell Jar. This small act of rebellion became the seed for Allen’s new collection, a suite of lingerie-infused house clothes that reclaim the domestic wardrobe while nodding to histories of care, control, and the women institutionalized on account of both.

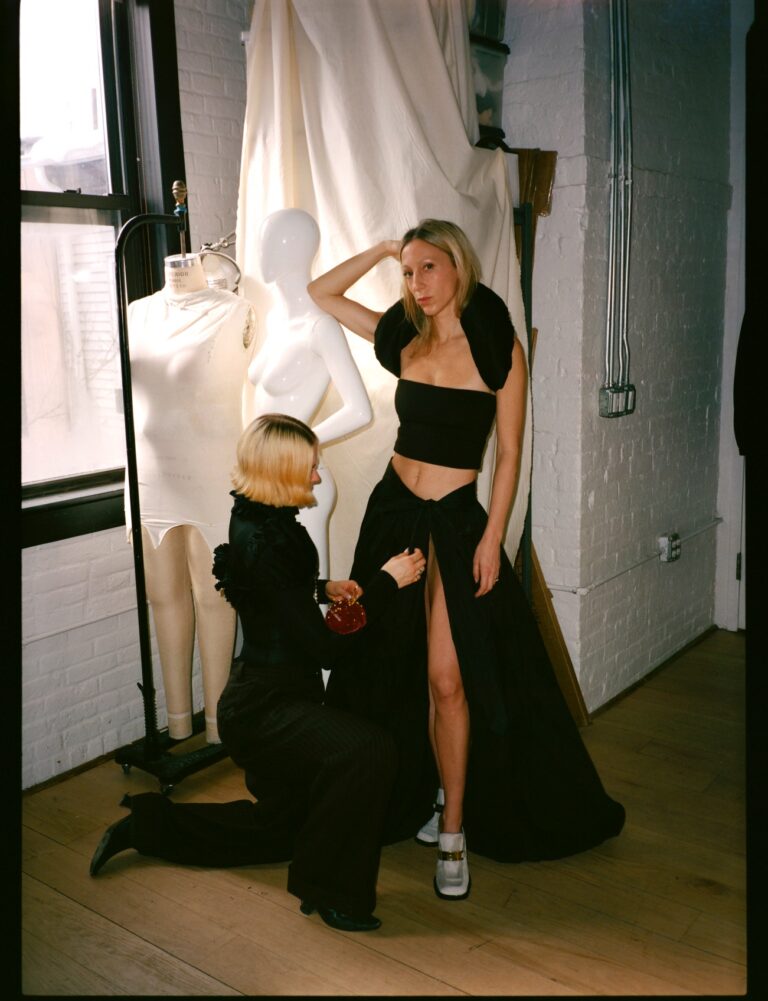

As with past collections, there is specificity to the colors and plushness of Allen’s latest garments, which she repeatedly trials on herself before sharing with a small circle of confidantes. “That’s the specialness of being really small—I get to have that quiet space to work through things on my own,” Allen confesses. “I am trying to take advantage of this time while I can.”

This intimate methodology ensures feel come first, which explains why silk lines many of Allen’s signature fleece coats. As we talk, Allen constructs an image of herself groping her way through racks of fabrics and vintage clothing like a chef shopping for the right melon.

Her path to certain shades is equally intuitive. Allen’s first trajectory—the ones that set her on the ascendent trajectory she’s navigating today—were characterized by hot oranges, vibrating lavenders, religious reds, and venomous greens. (She’s since added in a few plastic blues.) These colors are gathered from her travels, or found in tarot cards and paintings. “Color is where I infuse that mystical quality, which is really important to me,” Allen says. “I’m always attracted to something that is a bit wrong. There’s beauty in colors that you can’t quite place.”

This material seduction coupled with Allen’s Victorian-inflected tailoring is what has made It girls everywhere respond so rabidly to her output. (I’ve spotted Allen’s handiwork on devotees like gallerist Hannah Hoffman and writer-publicist Kaitlin Phillips.)

Optimistically, her meteoric rise can be read as a broader shift toward clothing maximized for clients’ delight rather than the calculated judgements of social algorithms. That’s not to say that Allen’s clothing hasn’t gone viral—check the respective instagrams of Ayo Edebiri and Charli XCX. It just hasn’t been at the expense of the women wearing it.

Over the past two decades, fashion has established a false binary: Chase a fleeting timeliness or retreat into utilitarian timelessness. Allen rejects both. Her clothes don’t worship at the altar of utilitarianism or taste. They slouch towards a more spiritual and mystical understanding of dressing—and perhaps more poignantly, the due comfort of the feminine body.

in your life?

in your life?