Earlier this month, I watched the New York– and Los Angeles–based curator and art advisor Mashonda Tifrere haul a 50- by 48-inch cardboard box into a spacious gallery outfitted with plush black couches and ottomans. Once Tifrere reached the center of the space, she placed the parcel onto the ground, opened it, and peeled back each layer of packaging expertly, like a chef unwrapping an onion.

Then Tifrere uncovered the object of her affection: An acrylic painting by the Nigerian artist Victor Ubah that depicts a woman wearing a headwrap and white button-down shirt. She stands on a terrace that’s surrounded by trees and turns her head to assertively meet the viewer’s gaze. Tifrere gingerly picked up the canvas, held it at arm’s length, and smiled.

“It’s beautiful in person,” she says, explaining that the portrait shows Toyin Ojih Odutolya, a powerful artist in her own right whose work has appeared in institutions from the Museum of Modern Art to the National Museum of African Art. “I collect [Odutolya’s] work, and [Ubah] told me that] she's a big inspiration him as well, so I was excited to see it in person.”

The piece, called Toyin at the Balcony (2022), is one of many on view at “To Each, Her Own,” Tifrere’s latest exhibition, which opened on International Women’s Day, March 8, and will run through April 18 at the West Village gallery Urban Zen. The show features 15 artists—Ubah, Akilah Watts, Alanis Forde, Chantel Walkes, Cydne Jasmin Coleby, Eniwaye Oluwaseyi, Ikeorah Chisom Chi-FADA, Jewel Ham, Johnson Ocheja, Lanecia Rouse Tinsley, Lauren Pearce, Marie-Danielle Duval, Megan Lewis, Monica Ikegwu and Robert Peterson—working in a variety of media, including painting and textiles. Each creator uses materials in unique ways, but every work on display is united by a single theme: female empowerment.

“For centuries, men have always painted women very sexually or submissively,” Tifrere says. “[These artists] are doing the complete opposite. [They are] painting women and young girls with so much power and strength and an element of nurturing, vulnerability, mothering, and emotion.”

Tifrere has always sought to highlight the work of female artists, so in 2016, she started ArtLeadHER, a program that seeks to amplify the work of female-identifying creators; and more recently, she founded Art Genesis, a platform that helps emerging artists.

“It’s important to center Black femmes simply because they have been denied access,” Tifrere said in a previous interview. “Giving artists an equal opportunity to thrive and create art, also to build sustainable careers, is central to the work that I do with ArtLeadHER and Art Genesis.”

The works in “To Each, Her Own” build on the mission of ArtLeadHER and Art Genesis because these portraits weave compelling narratives about female introspection. This was clear to me when I walked through the gallery because it was filled with intimate portrayals of Black women doing everyday activities, like lounging on the beach, reclining on a couch, or posing in front of a bathroom mirror. Standing before these canvases, I felt comfortable, especially because Urban Zen isn’t a sterile exhibition venue with all white walls and stiff gallery assistants. No, it has the ambiance of a large living room replete with sofas, soft lighting, and wooden tables, the ambiance of a home where I can sit with a piece of art that depicts someone who looks like me. The fashion designer and philanthropist Donna Karan wanted to create a site for such shows when she founded Urban Zen, which is why she and Tifrere have had a fruitful creative partnership for years.

"I’m so happy to have ArtLeadHer back at the Steven Weiss Studio where my husband created all of his work,” Karan says. “With the opening of “To Each, Her Own” we continue to connect the dots by showcasing a diverse group of talented artists from all over the world. After a year hiatus, due to the pandemic, this will be our 5th year working with Mashonda. [She] represents such amazing young artists, and it’s an honor to watch them grow […] From one woman to another, I’m honored to have her back here celebrating International Women’s Day and month.”

Lauren Pearce—an Ohio-based artist included in the show—is one such person who Tifrere represents. The two connected in 2019 when the curator discovered Pearce’s work through a hashtag on Instagram and asked if they could schedule a meeting. They hit it off immediately, bonding over shared interests like food and their experiences as single mothers.

“She's the first artist who I've ever represented wholly,” Tifrere says. “Last year, I asked her to write me a list of everything she wanted for 2021. On that list, she said, ‘I want to show at Art Basel, have my first solo show in Palm Beach, and show in LA.’ I made all those things happen for her.”

Pearce concurred with this, adding that Tifrere has always accommodated her needs.

“She took into consideration that I'm a parent as well,” Pearce said. “I can't operate like everybody else, and she has always allowed me to maneuver even if it's last-minute thing—she knows I'm going to get it done.”

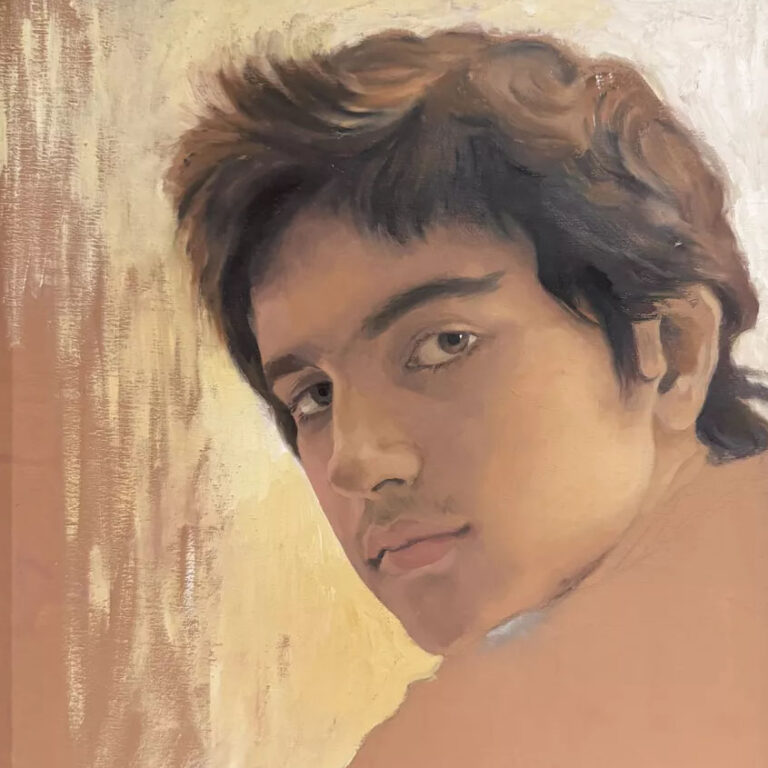

Tifrere’s patience paid off, so Pearce was able to contribute several works to the show, including Last Light (2020), which shows a dark-skinned woman donning a shirt decorated with rhombuses. Another Pearce painting, Our Way to Fall (2022), is a salient portrayal of a person wearing a durag. Initially, Pearce had intended for this person to be a man, but many viewers perceived the painting’s gender identity differently.

“The individual is supposed to be a man, but some people think that they look like a woman,” Pearce says. “So, I said: ‘You know what? I feel like whatever you see is going to be your own,’ which I kind of like. There is no right way to interpret it. I also think in masculinity is [a fraught concept.] Just because you are masculine doesn't mean that you can't wear soft clothing.”

Other artists in the show have made similar musings about race and gender. For example, Peterson’s painting Tomorrow’s superHERo (2022), depicts a striking scene of a young girl and her family, challenging the pernicious narrative that Black families are broken groups of people incapable of protecting one another.

“The family behind her was a little bit blurry,” Peterson says. “The point of that was to make sure that she was in focus. She appeared closer to you because the story of the painting is about her, but she wouldn't be able to become who she is without the support of the people behind her.”

Perhaps placing a painting like this in a fine art setting can expand our perceptions of Blackness. When speaking with Peterson, he posited that making room for such works could allow us to tell more positive stories about Black life in America.

“I hope that [the show] inspires other people to tap into who they are and to be able to paint their truth,” Peterson says. “[Artists should be] honest to themselves and not worry about trying to [always make a sale]. They should create something that makes them happy. And I think that it reads in the work. I'm honored to be in the show.”

in your life?

in your life?