The future doesn't exist for Alex Sewell. Not because he casts his eye exclusively to the past—though nostalgia and memory are central to his practice—it's simply that he accepts the apocalypse as inevitable. And with end times approaching, what's an artist to do? Judging from his show "When I Wanted Everything," up now at TOTAH in the Lower East Side, the 30-year-old's response might be: embrace the world before it burns to the ground.

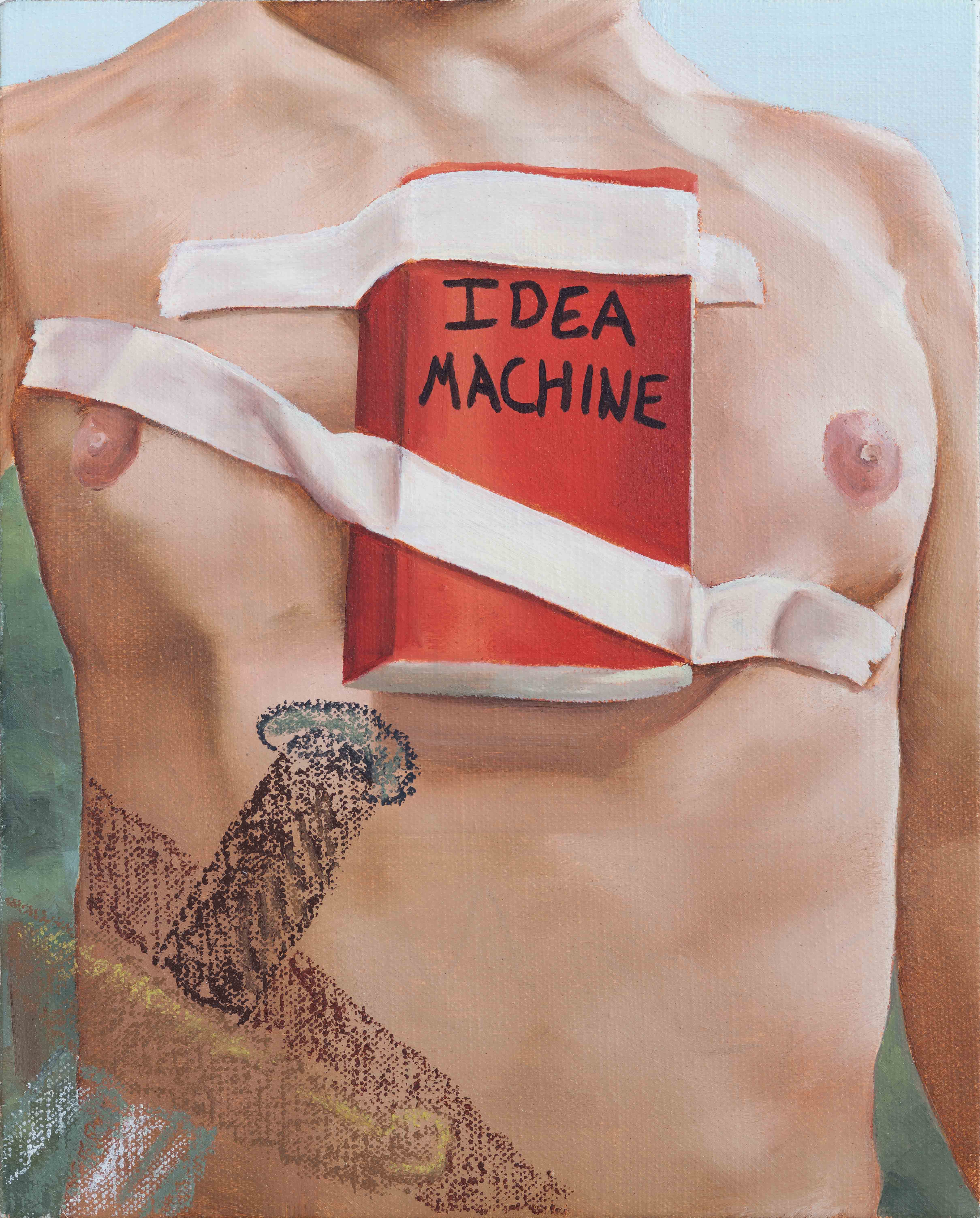

That embrace is qualified by a persistent melancholy in the artist's oeuvre. His oil canvases are full of references to a '90s suburban childhood—action figures, VHS tapes, "Final Fantasy VII"—as well as Rube Goldberg-esque contraptions of impossible physics and lo-fi charm. That impossibility is crucial, always pointing upward and away from cynicism. It gives his paintings both a contagious exuberance and an entrance point for the viewer.

Artists who navigate between personal and cultural cosmologies risk opacity, forever working within a closed system of symbols and referents—see Matthew Barney or Samara Golden—and Sewell acknowledges as much. In a recent studio visit, he said he began using the action figures as a nod to the unavoidable narcissism of the artist. People assume a level of self-regard—why not answer with a wink? Sewell now sees the figures and toys as part of his vocabulary, along with the painter's hand, which appears scaled-up in many of his works. This is a bit of bravado, as Sewell's technical bona fides are strong. The flesh in these paintings looks like John Currin under drugstore fluorescents.

While the paintings in the new show trade in sentimentality, they also gesture toward art history with motifs and markers from the Renaissance, much of it gleaned from recent trips to Venice and Rome. When I asked about inspirations, he cited Roman travel shrines, Jung's work on dream time, and the fiction of Ocean Vuong and David Foster Wallace.

These disparate sources all touch on loss, an undercurrent in Sewell's work balanced by a secularist's appreciation of the sacred. Seventh Trumpet (2018-19) depicts a meteor show at top, scribbled over by a bearded deity vomiting a sword of fire. Bisecting the canvas is a storyboard map of a tropical Eden done in the style of a Super Nintendo-era video game, while below is a geologist's rendering of the earth's mantle. The picture plane is complicated by trompe l'oeil burns revealing a stretcher bar, a taped-up child's sketch of a domestic scene in colored pencil, and a tiny spaceship.

Again, this is all rendered in oil. Sewell is a happy illusionist and a sly traditionalist: pencil sketches, acrylic marks, and spray paint are all faithfully and painstakingly rendered in that most classical medium. (He said figuring out the spray paint was difficult, and almost poisoned the air in his studio.)

Throughout our studio visit, Sewell's comments on the art world kept returning to the idea of time running out. He has an autodidact's work ethic—Sewell opted to forgo an MFA—and he paints as if determined to find and exceed some personal limit. He says the TOTAH paintings are "an homage to the things I can't escape."

In this way, Sewell's art is the art of climate catastrophe without being about climate catastrophe. It's what you want on the museum wall as the flood smashes through the windows.