Peggy Levison Nolan’s first solo museum exhibition, “Blueprint for a Good Life” at Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum FIU, opens with an image of her daughters seated on a ratty couch destined for the trash dump. Taken outside of the federal housing apartments where Nolan lived with her children, the photo captures the essence of girlhood trapped within the confines of limited means: Stella and Gertrude sit with their legs folded, their bodies draped over the sofa, enticing us to imagine what sort of mischief might result from such boredom. Untitled (Broke Down Couch) (1987-1988) is rife with innuendo characteristic to Nolan’s body of work: Though the artist borrows influences from street photography, she captures the intimacy of home; she documents her modest life alluringly, a hint of the treasure that lies within its simplicity.

Devotees of Nolan’s work are likely more familiar with her color photography, which captures fleeting moments of family life interwoven with dialogues around class, time, and affection. But “Blueprint for a Good Life” is an opportunity to dive into the origins of her work, revealing the artist’s inherent proclivity for capturing candid moments with tenderness. Through her mother’s gaze, we see a family doing the best they can with what they’ve got, and a woman bent on discovering her family from behind a lens. Though Nolan makes work focused on the domestic space like other women photographers Sally Mann, Melissa Pinney and Tina Barney, curator Amy Galpin points out that those women mostly documented an upper middle class life.

“[Nolan] lived in HUD housing, but there is a lot of happiness and good times in these photographs, despite facing economic challenges that happen and especially in a big family,” she says.

Nolan’s path to photography was quite unconventional—her father gave her a camera when her youngest child was three years old, and she was instantly obsessed. “I got so hooked you can’t even imagine,” she says, and ultimately wound up returning to school to pursue a BFA. Nolan, then in her 40s, stood out among her classmates at Florida International University, who often prodded her about the difficulty of being a mother living in a low-income household. “For her, it was never anything to be sad about; she loved it,” says Galpin. “She married this dedication to the domestic space with her art.”

Her enduring connection to the university—Nolan received both her BFA and MFA from FIU in the early 2000s, and taught there for decades—was a compelling motivation for Galpin, who wanted to elevate the photo department’s historic talent while offering a relatively under-the-radar artist her first museum solo. Honoring the craft within the 20-some silver gelatin black-and-white photographs was important to the curatorial team, with Peggy’s work displayed without any sort of pretext. As the 77-year-old Nolan, who lacks any sort of pretentiousness, playfully says: “The photographs are easy and digestible like animal crackers; no deep art speak required.”

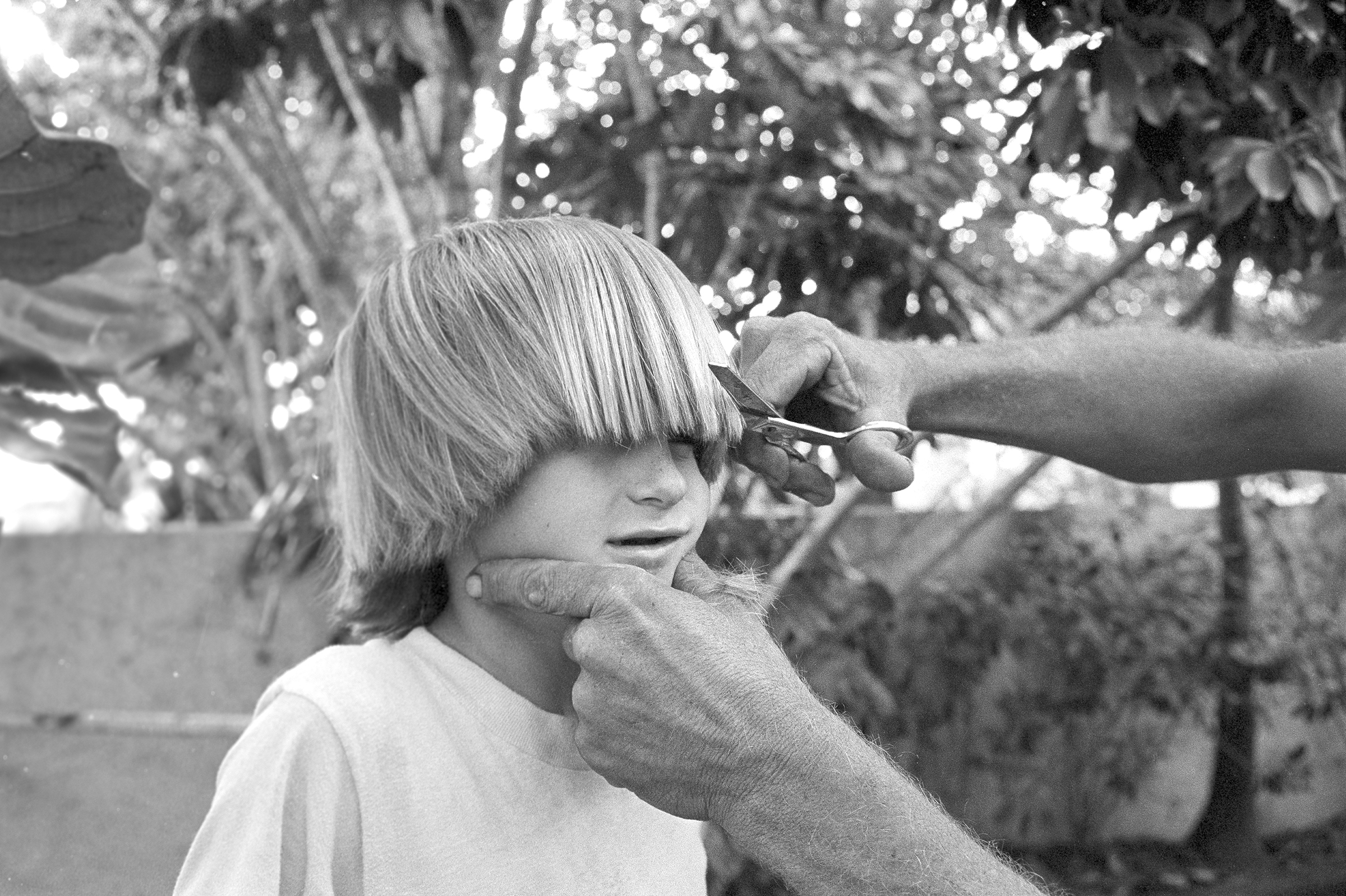

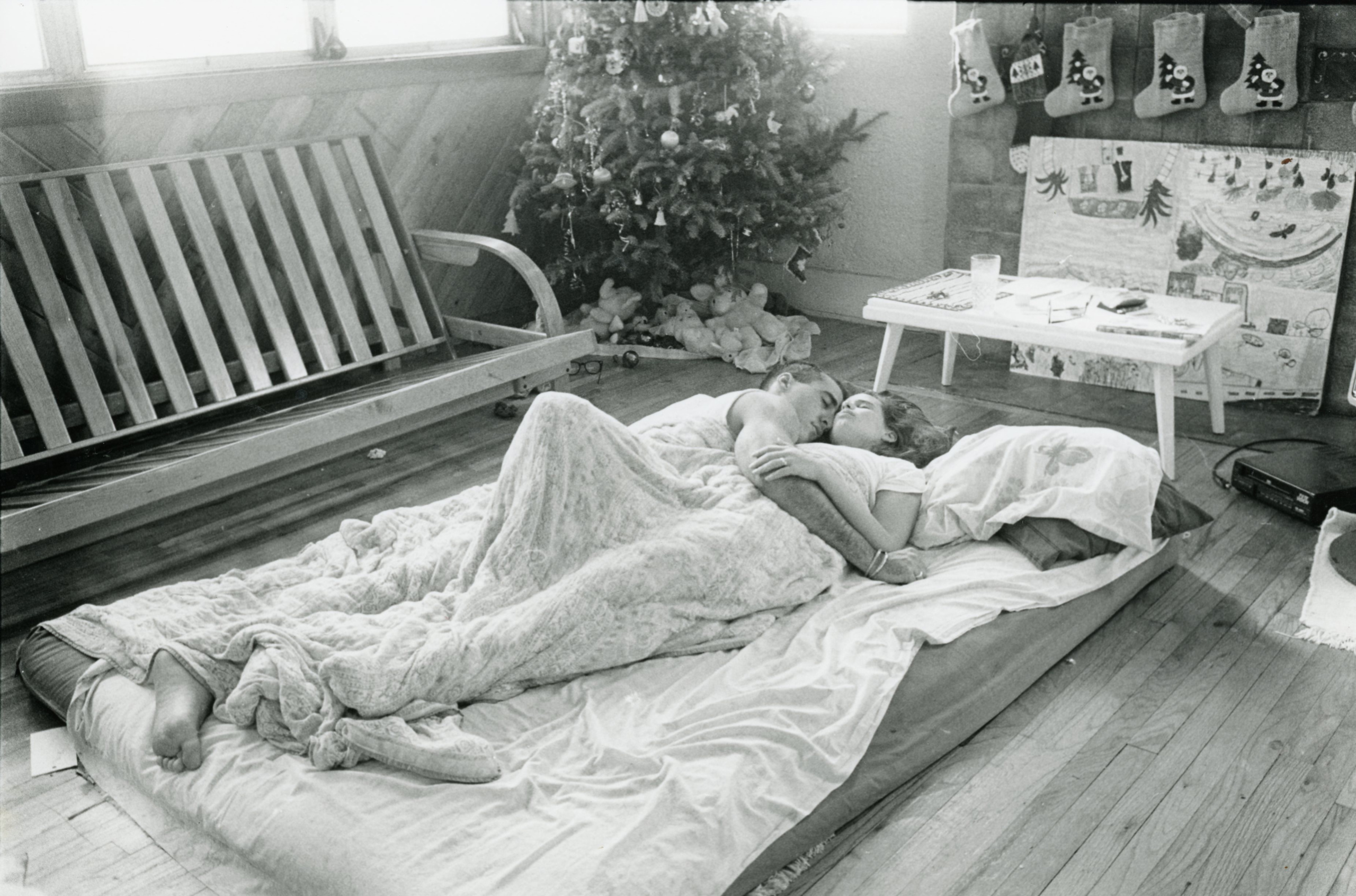

They did, however, take care to group images according to Nolan’s fascination with documenting certain subject matter: “Love Play” is a sensitive veer into voyeurism as Nolan captures images of her children learning how to love. The photos feature her children enveloped in caresses and experimenting with romantic relationships, many of which ultimately ended but no less marked the exuberance of budding love. “Marking Time” reveals a similar dialogue about youth and aging, with images like Untitled (Bowl Cut) (1986) and Untitled (Belly Ring) (1994) offering a fleshy materiality that tips the photographs into the conceptual realm.

Though all of the scenes in “Blueprint for a Good Life” are rather mundane, they display Nolan’s ability to transform an everyday moment into one that reveals the depth of the human experience. From joy to melancholy, boredom to desire, sagging bellies and shirtless skinny teenagers, Nolan celebrates the trivial instances that make up the fabric of a life lived.

“The thing about photography is that it’s never actually about what’s happening,” says Nolan. “There’s a remarkable transformation from what you think you saw to what you get. And that’s the addicting part.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.