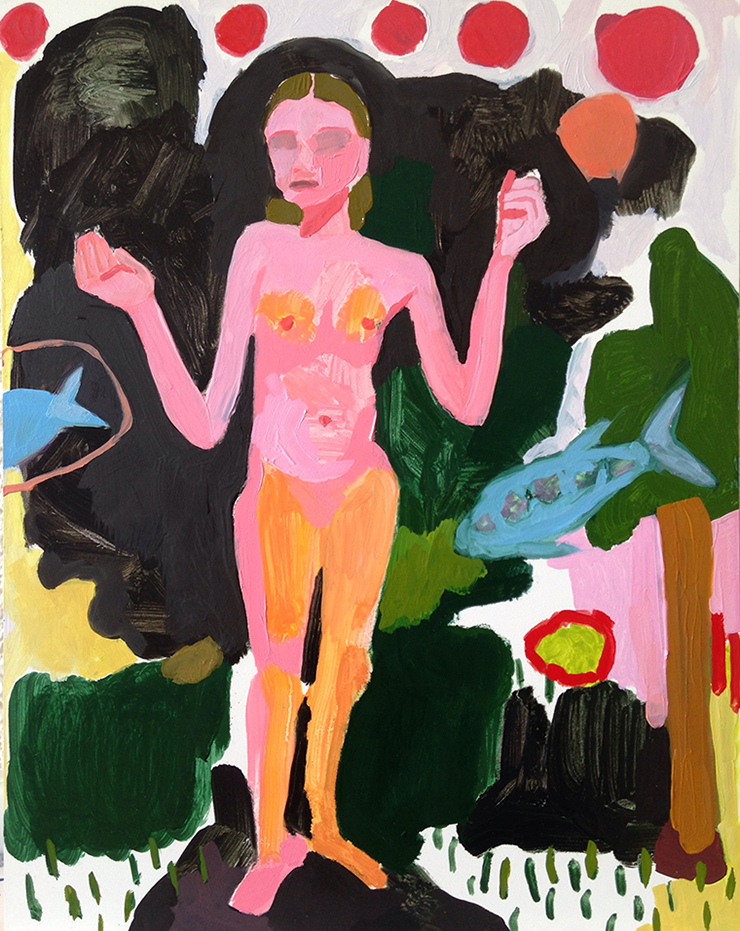

For our latest Cultured Commission, we tapped Brooklyn-based artist Kimia Ferdowsi Kline to create an edition of her Andromeda and Two Arabian Fish. Because her family left Iran before she was born and cannot return due to persecution of the Baha’i faith, Ferdowsi Kline remains fascinated by the images, language, and literature of a place she can never visit. In past series, she has created mythical and fantastic Iranian landscapes that are part fact, part fiction. In her latest series of paintings, which debuted at Detroit’s Elaine. L. Jacob Gallery on April 8, the artist drew inspiration from the ancient Persian book of fables, “Kalila and Dimna.” Here, the artist talks about Persian garden design, Matisse, and using Instagram as a window into Iranian life.

Historically, a large portion of your paintings have been inspired by the landscapes of Iran, a place your family left and you’ve never been able to visit due to persecution of the Baha’i faith. Where do you pull from to piece together these images? It began with a residency in India, where I lived and painted for 8 months, and was for the first time exposed to Persian garden design. Being there is the closest I’ve come geographically to Iran, and seeing the gardens firsthand gave me enough visual information to begin exploring these themes. I also pull from family photos and stories I grew up hearing about Iran, so oral history is a big part of it. My imagination tends to fill in the gaps. And most recently, social media has played an increasing role in constructing these images. Before Instagram, I found it difficult to find images of Iran that weren’t of bearded men in turbans chanting, “Death to America”, or women covered head to toe in chadors. Through social media networks like Instagram, I’ve been able to connect with Iranians who share photos of their daily lives, both the beautiful and the mundane bits. Seeing these images has become a daily practice of mine, something I experience each time I look through my feed. Finally I have visuals other than the ugliness I see on the news, which has allowed me to come a little closer to understanding this place.

You’ve referred to your paintings as “reconstructed, fictitious memories.” What does it mean to paint such mythical, phantasmagoric, paradisal landscapes from found images or imagination? Are you pointing to the constructed nature of memory itself, of myth itself? Exactly. Memory itself is both fictitious and real. Science has proven that our memories are actually quite malleable, and imagination and emotion always play a role in shaping them. When I began relying more on my imagination to make these images, and less on physical reality, it made sense that the way I was painting, moving between abstraction and reality, was directly related to the process of making a memory.

In this new show, As Above, So Below at Elaine. L. Jacob Gallery, it seems like you are focusing more on figures than on landscapes proper, with paintings like Andromeda and Two Arabian Fish and Two Jackals. These paintings are inspired by the ancient Persian book of fables, “Kalila and Dimna.” Were these stories important to you as a child? I wish I had known about these stories as a child--I came across them as an adult while researching Persian miniature paintings. I kept noticing that my favorite miniatures were from the same book, namely, “Kalila and Dimna”. I was actually embarrassed once I realized how renowned these stories are in the East. I constantly feel like I’m still catching up, trying to learn more about a place I can’t experience firsthand. There’s a certain level of cultural amputation that occurred when my family left Iran. Most of my work is about repairing this sense of loss, of bridging the gaps in my knowledge and understanding. It began with trying to understand the most basic thing about a place — the physical landscape. And it’s now evolved into exploring the literature and language.

You also mix in things from your own life with the fables. What is the significance of doing this? I think it’s an attempt to explore the question of the importance of the unique individual in larger society. Relating my individual experience to the experience and wisdom wrapped up in these stories calls to mind the idea that the very intimate contains the vast, and the endless vast universe is made up of smaller bits and pieces. This is where the title of the show comes from, “As Above, So Below”. These stories were written for everyone on a macro, universal scale. But they aren’t relevant until each individual absorbs them and relates them to their own specific lives.

It’s interesting to think of formal similarities with Matisse, in terms of color and a relationship with abstraction — I’m thinking in particular of a work like his “Le bonheur de vivre.” Is Fauvism a big touchstone for you in a formal sense? Yes, definitely. I take a lot of inspiration from Matisse, and the Fauvist premise of using expressionistic color over representational or realistic values is something I’m always thinking about in my work. Color is everything for me — it’s what I spend the most time considering. If this yellow is slightly cooler, what will that do to the emotional impact of this piece? If that red is hotter, how will it affect the composition and the way my eye moves through the painting? What do I put next to this blue to really make it sing? These are the questions that consume most of my time, and I’m guessing the Fauvists were asking very similar ones.

Obviously you have a critical eye towards these mythical or mythologized representations of the landscape, of female figures. As someone whose family comes from Iran, who speaks the language, who is very conscious of that history, why is it useful to use the language of early modern painting to depict your subject matter? Painting is an incredibly flexible medium and has this alchemical ability to absorb and unite seemingly disparate ideas in one picture plane. Its capacity to simultaneously hold so much complexity in one space makes it really well-suited for what I’m trying to do. It allows me to seamlessly move between abstraction and reality, similar to a stream of consciousness thought process, as opposed to a more didactic way of understanding.

The question of language is an interesting point, however. In the West, we tend to compartmentalize and separate the visual from the written. But throughout the East it’s generally one and the same. The idea of the painted Persian miniature, for example, is synonymous with poetry and language: calligraphy itself is a form of painting. All words and letters are fair game in Persian and Arabic script, with poems and stories morphing into nightingales and stars on the regular. I suppose it makes sense that I would conflate these two forms of communication in my own work.

To purchase Andromeda and Two Arabian Fish, visit Artsy.net/Culturedmagazine.