It was 1964, New York City. The sixties was a time for exploration, experimentation and expression—all in the name of freedom. It was a new era, and people were drawn to the unknown, eager to learn, try and taste things that they had not before. Alain Jacquet’s show of his Camouflage series at the Alexander Iolas Gallery could not have come at a better time.

In 1960 Jacquet, living in Paris, met John Ashbury, a poet and writer for the New York Herald Tribune, who quickly brought Jacquet into the art world and the American expatriate scene. One year later Jacquet painted his Cylinders, which he saw as the beginning of his art. They were liberal paintings that broke with the gestures of Abstract Expressionism. The colors were not mixed, but juxtaposed. At the same time American artists like Frank Stella were using juxtaposition but without mixing colors. Jacquet’s following series, Images d’Epinal, followed this use of juxtaposition of colors. At the end of 1962 and the beginning of 1963, the journal Art International was the first in Europe to publish reproductions of American Pop Art, exposing Jacquet to the work of Johns and Liechtenstein in color for the first time. Reflecting upon what he had seen, Jacquet decided he would remaster their works as well, beginning a conversation between artists.

When the Algerian War had begun, Jacquet began to plan how he could avoid becoming a soldier. Born 1939, the year of the start of World War II, war was something all too familiar. In 1962, when he received his summons, he set his plan in motion: He decided to lock himself in his small Parisian apartment, eat one hardboiled egg a day and see no one except during brief outings at the wee hours of the night, around three or four in the morning, when he would walk around Pigalle, among the hookers and drug addicts. For one month he followed this routine in hopes of becoming a bit mad, so that when it was time for his examination he would be marked as unfit. Sure enough, the day came, and Jacquet excelled in his role. At the end of the examination, he was sent home deemed unfit to serve.

In 1963–64, while French soldiers fought the last battles, Jacquet produced his Camouflage series, his own modern interpretations of the masterworks of the past. Each work in the Camouflage series consisted of two images superimposed on each other to create a new image, brought into view through the juxtaposition of colors. The first image was a historical work, and the second image carried an ironic and critical message, making the work more of a question than an observation. He took Sandro Botticelli's famous Birth of Venus and Leonardo Da Vinci’s La Cène, and transformed them into original Jacquets. He interpreted Jasper Johns’s Flag (1955) in Camouflage Jasper Johns, The Voice of his Master, in which he painted not one, but three flags superimposed on each other with a dog barking into a gramophone, below which was written, “La Voix de son Maître.”

Known for his artistic wit, Jacquet continued to push the limits through his sense of fashion. For the opening of the show of his Camouflage series, he had made a two-piece silk World War II parachute suit with camouflage patterns: extremely daring, as camouflage had never been taken out of the context of war before. He spent the night of the show mingling and discussing his works with Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and other key figures in the American scene. His work was well appreciated in the United States before the summer of 1964, but after Rauschenberg won first prize at the Venice Biennale things began to shift, and foreigners were pushed away from the developing “All-American” Pop Art movement.

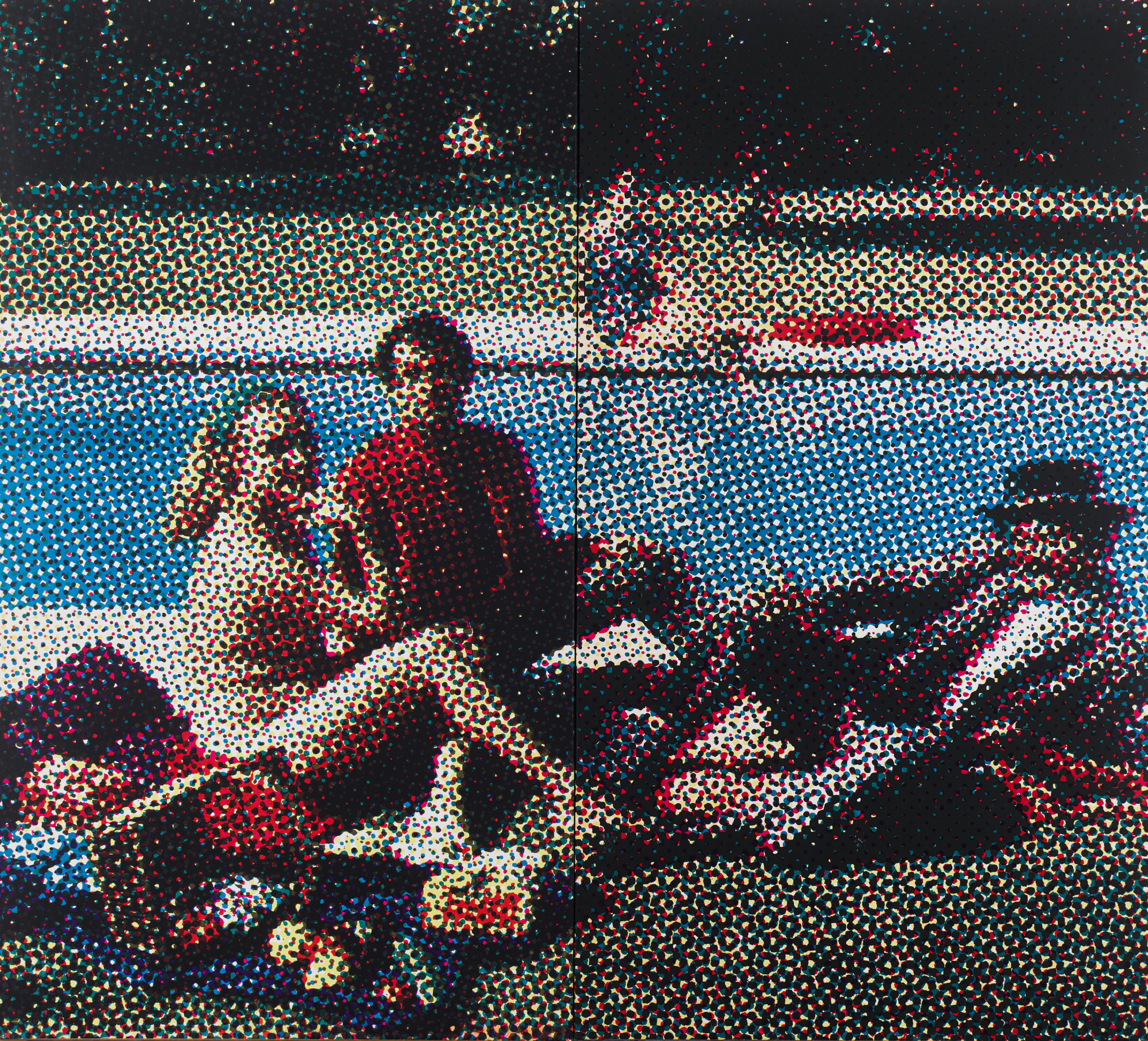

While he continued to draw inspiration from the old masters, in 1965 he made the process completely mechanical, using only superimposed primary colors, for which he was dubbed the founder of “Mec Art.” This new process utilized of machines to create limitless art. He became interested with scale, playing with the audience's vision, making things appear abstract up close but clearer the further one steps away. For the Trame series (1964–65), Jacquet used actors to stage cinematic versions of scenes from the history of art, such as Édouard Manet’s infamous Déjeuner sur l’herbe and equally infamous Olympia, the famous portrait of Gabrielle d'Estrées and one of her sisters that hangs at the Louvre and Ingres’s La source.

During this time, all paintings were frontal and two-dimensional. Even the paintings of Lichtenstein and Warhol from ’62-’63 were entirely on one plane. Jacquet introduced new dimensions into painting.

Soon after, Jacquet began to take interest in sculpture and braille, which occupied him in the 1970s and out of which came his Visions of the Earth series. “The crystal ball symbolizes the possibility to see multiple images in the same piece of stone,” he explained. “So I realized I needed an image quite simple. The Earth, where I am, is finally what interests me the most, why not use it as my subject?” In 1969 American astronauts set foot on the moon for the first time, and NASA produced the first image of the Earth. Two years later, Jacquet realized The First Breakfast, where he screen-printed NASA’s image in concentric circles. He placed the center of the circles on the Pyramid of Cheops. He then began to question what he could read in The First Breakfast, just as one reads into a crystal ball.

For the next twelve years, he created Visions of the Earth. Returning to the brush, Jacquet was able to paint directly from his subconscious, influenced by Carl Jung’s writings and imagery and the collective unconscious. Finding hidden images within the photograph, Jacquet painted around these, making them more present, while still camouflaged. While the struggle to be recognized and accepted in America continued for Jacquet, who was living in between New York and Paris, his work did not suffer. In 1984, when Warhol realized The Last Supper in monochrome camouflage, it was extremely frustrating for Jacquet who had originally created La Cène (a detail of the Last Supper) in camouflage in 20 years earlier, exhibited at a show that Warhol himself attended. While many artists took ideas from each other, Jacquet had had always given credit to the artists he borrowed from—Lichtenstein, Johns, Picasso, Matisse and—even as he created something new, which Warhol had no intention of doing for Jacquet.

In 1993, the Centre Pompidou held a retrospective for Jacquet, and a couple months later I was born: Gaïa, meaning Mother Earth, his own living, breathing creation that fit perfectly into his life’s exploration of the universe. The retrospective was important for Jacquet, as it was the first time the range of his vision was displayed. The Truth Coming out of the Well, a rather erotic depiction of human evolution, hung front and center, asking what must be done to produce and evolve. Jacquet decided to take sex, something that had always been a bit taboo, and enlarge it and make it inescapable for viewers, forcing them to confront something natural, questioning their own discomfort. Using imagery that is archetypal, meaningful to everyone and representative of Earth, Jacquet pushes viewers to find concrete elements in what can appear abstract. The images and elements that appear in the Visions series are well camouflaged, often requiring the viewer’s close attention to discover the hidden treasures. Jacquet’s paintings are not easy, simply aesthetically pleasing paintings, as many American Pop Art works were. Instead, they are demanding and intricate, requiring viewers to train their brains to look further than just the surface.

I remember a rather erotic painting hung in my bedroom during my childhood in Tribeca, a painting done years before my father met my mother, Sophie, a prediction of their encounter and their eternal bond. It was a circular painting of a squirrel and a woman depicted from behind, naked with a very large backside, riding a bicycle with the seat half inside her. I must say I did have an interesting childhood. My father would take me to nudie beaches in Saint Martin, teaching me from a very young age that the human body was nothing to be ashamed of; it was simply an aspect of life. The freedom and creativity that surrounded me from the day I was born, brought up by two artists, led me to be the person I am today—never ashamed of who I am, what I have done or how I choose to express myself. Of course, there are things I’m not necessarily proud of, but if those things would not have happened, I wouldn’t have learned from them. It took me many years to truly appreciate the art that surrounds me on both sides of my family—Matisse and Jacquet, but there is no question that it has inspired every aspect of my life, my own creations and my vision of the world. While I haven’t had the nerve to start painting, I’ve never felt such an urge to begin as I do now. Who knows what it will lead to, but in the meantime I will continue to create in fashion and design, mediums I’ve always felt closely connected to. Pier 69 is another project I am working on, very close to my heart, which will captivate the essence of Gaïa, projecting my own visions of this Earth, hoping to inspire and create a collective consciousness of positivity and change for the future, evidently through art.

Throughout my childhood, in the 1990s, my father worked on his last series, the Donuts. He used computers, something completely new to him at the time, and very slow, to create images that appeared to be in outer space, in which planets morphed into the shapes of donuts and hot dogs—no coincidence, the two fitting together as one. La Danse, a play on Matisse’s famous work, is a collection of free-floating space donuts dancing through the cosmos. Mars and Venus, another clearly erotic work, was a hot dog halfway through a donut-shaped Mars, a continuation of Jacquet’s theme of our universal point of creation.

When we look at Jacquet’s work as a whole, we can see a strong backbone and an evolution of ideas. He began by painting with all colors, which carried out successive syntheses from primary and secondary colors to black and white. Then followed work that no longer evolves linearly, which is where the computer was introduced, to make way from new possibilities of creation at the technical level. Alain Jacquet passed away in 2008, at the age of 69. Unfortunately, he could not continue on his work or live to see the possibilities he could have had today. Jacquet’s influence made a mark on the history of art, inspiring an endless number of artists, myself being one of them. A genius, he created an extraordinary oeuvre, one which has not yet gained its full recognition, but certainly will in the years to come.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.