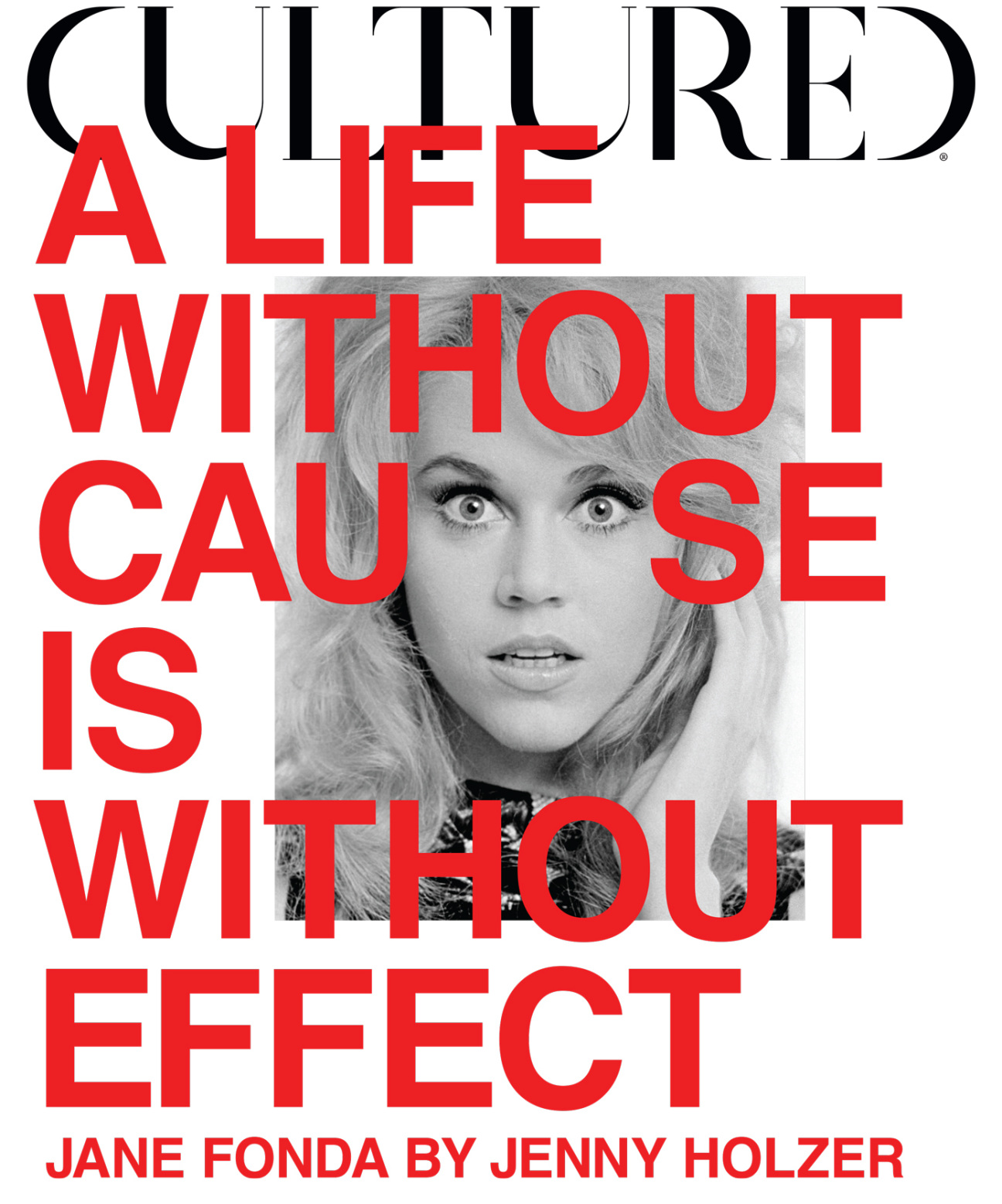

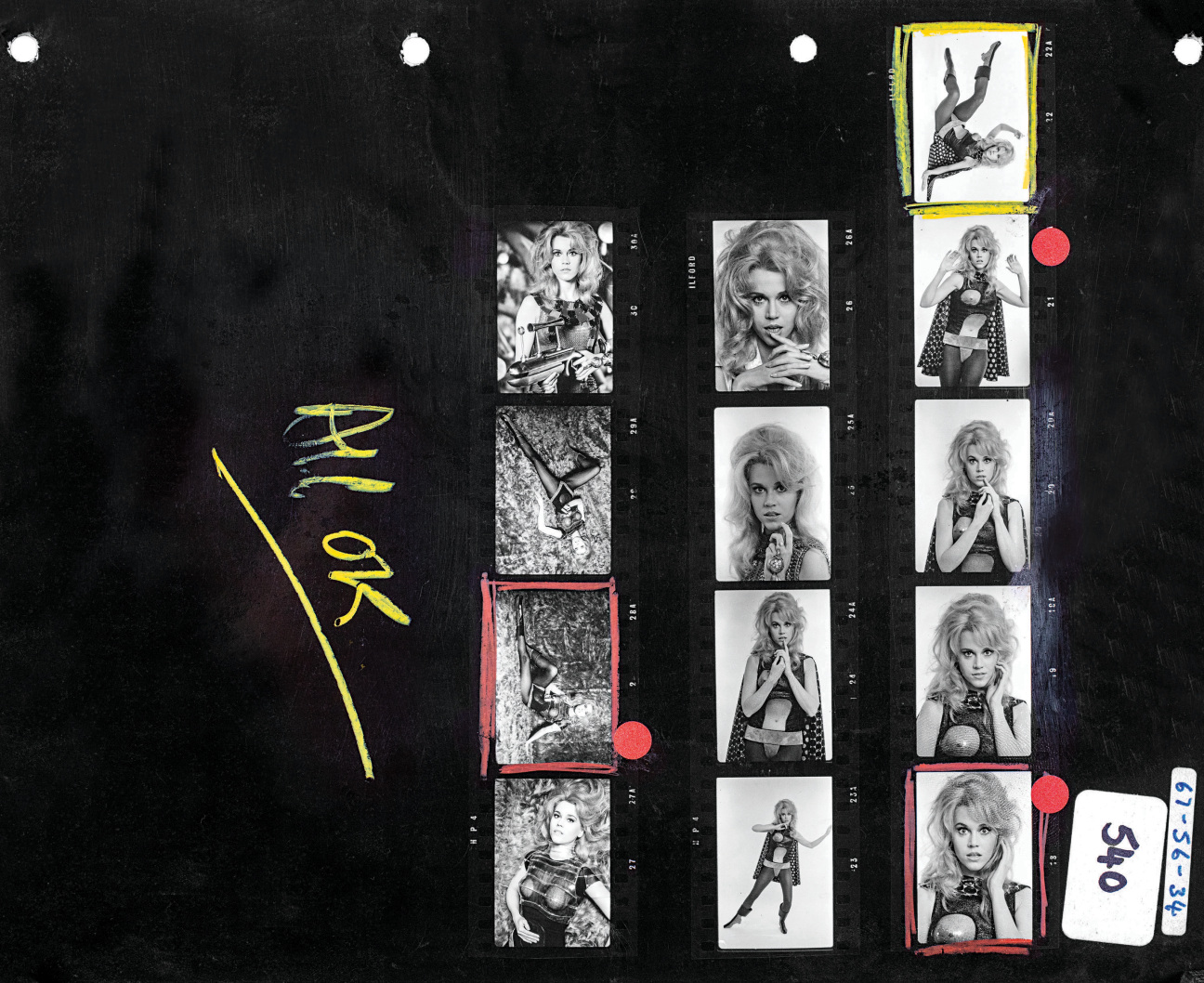

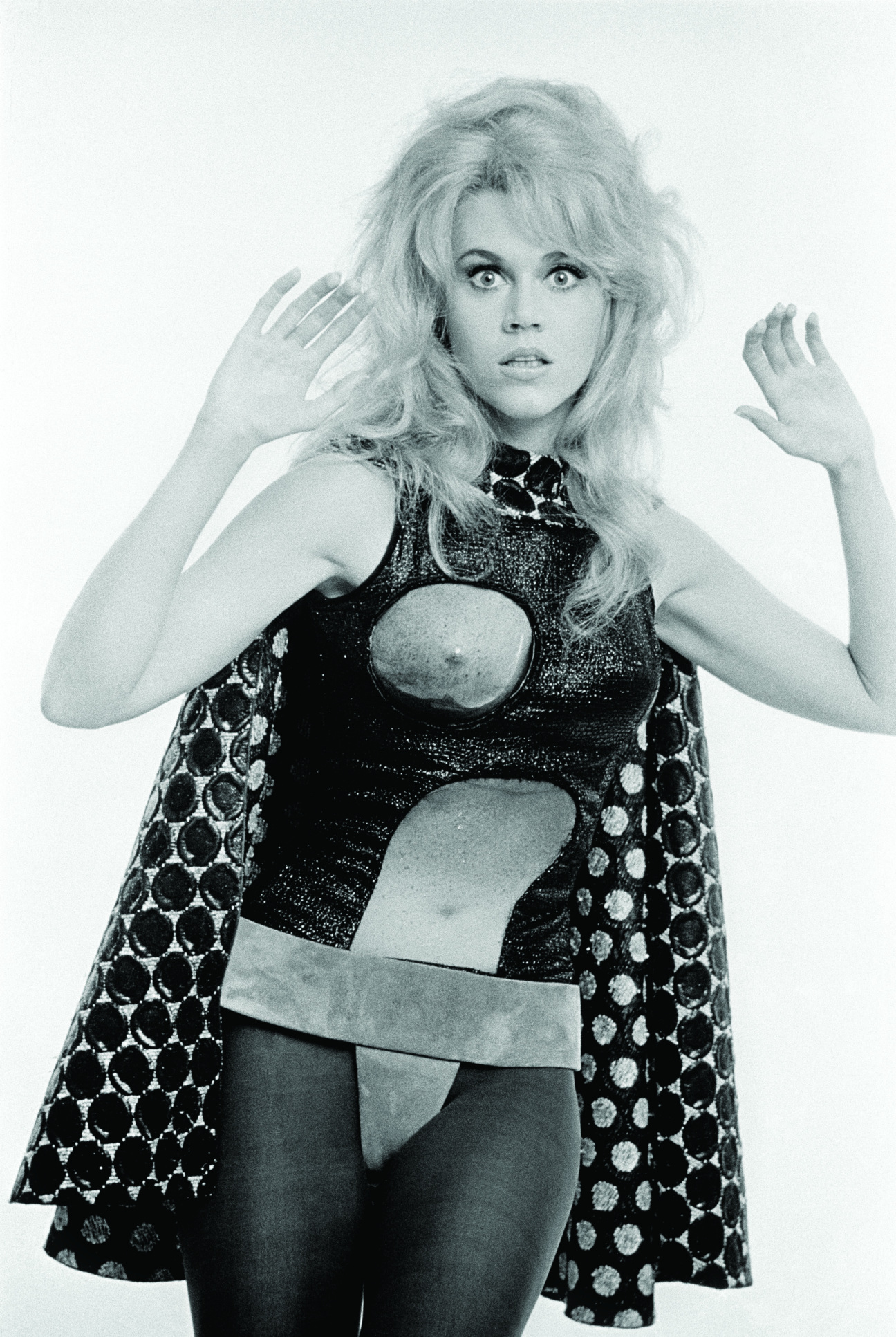

Through experimentation in performance and projections, Jane Fonda and Jenny Holzer have significantly impacted our cultural thought. Timed with her long-anticipated solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in New York, the artist encounters the star of Barbarella—choosing unseen footage from the archetypical 1968 film to reimagine its heroine as a superstar—for a legendary dialogue about protest, privilege, and perseverance for Cultured's Living Legends issue.

Sarah Harrelson: It is such an honor to be speaking with you both today. Thank you for making the time to be part of Cultured’s 10-Year Anniversary Issue. There is so much to get through in a short time, but to start I am curious to hear from you, Jenny, about when you first became aware of Jane as an activist.

Jenny Holzer: I was lucky to become aware of Jane when I was becoming aware in the late’60s. The Vietnam War was in front of us. I thought the war was tragic, and I was curious what able people were doing about it.

Jane Fonda: How old were you then, Jenny?

JH: Nineteen-ish. I marched in Washington, but that wasn’t enough.

JF: You were a good deal younger than me.

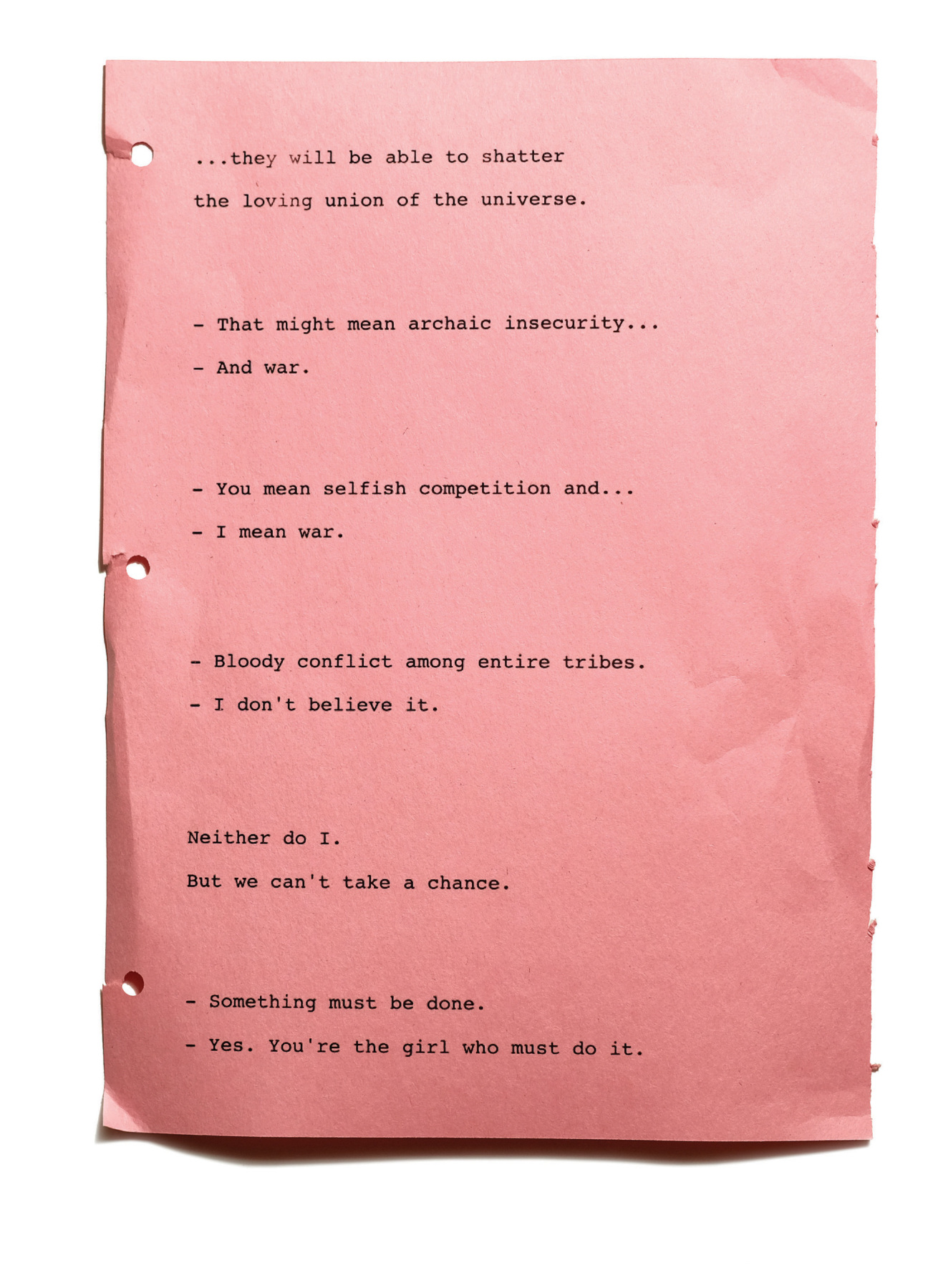

Barbarella courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

SH: I think you guys are 13 years apart. Jenny, you were born in 1950, right? And Jane, in 1937?

JF: Yes, I was.

SH: How impactful do you think this early act—marching—was on your own ideas of political expression?

JF: Marching was important and remains important. We have so many tools in our toolbox, and we must learn to use them all. Marching is certainly one of them. Civil disobedience is the next step after that, right?

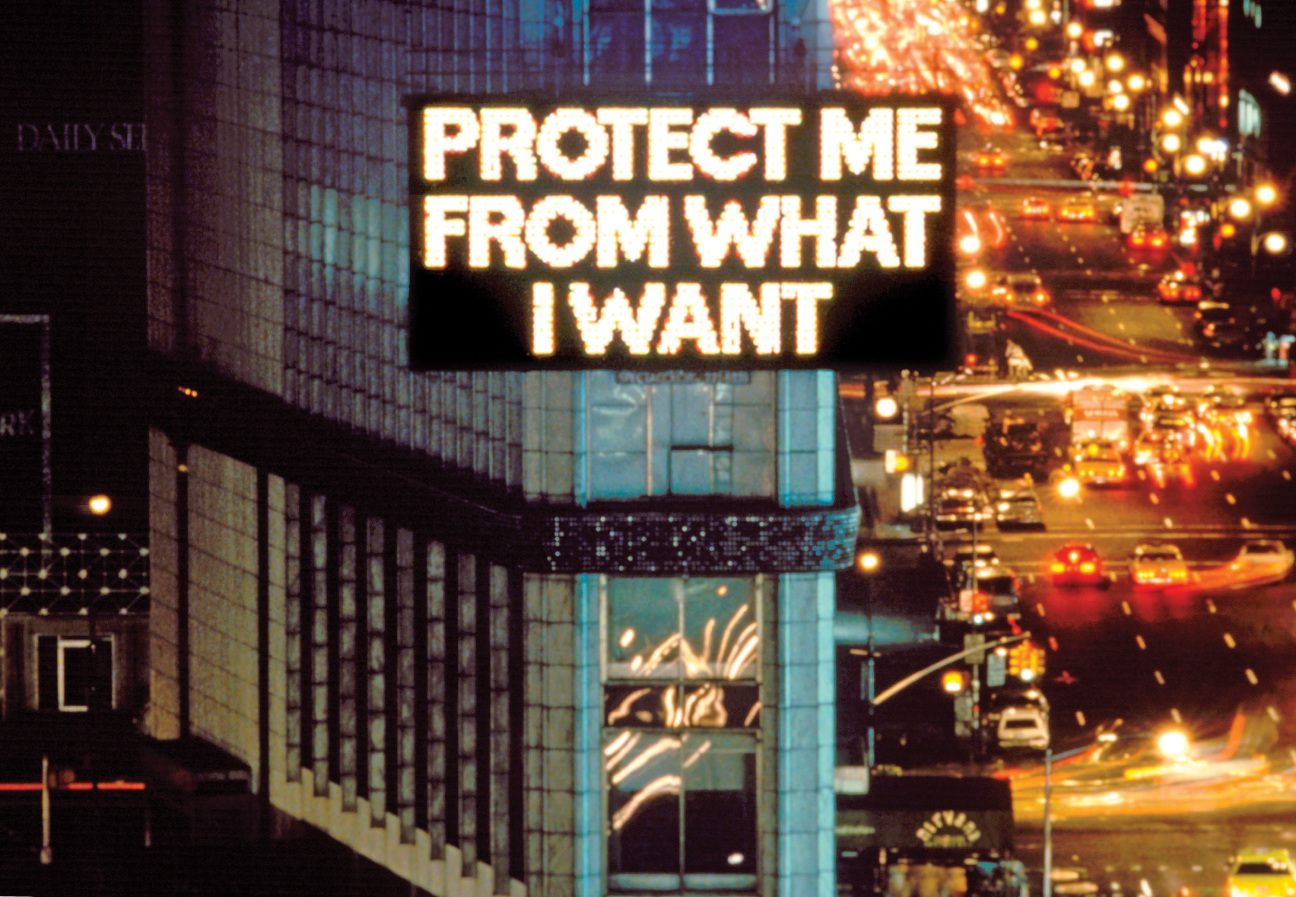

JH: Civil disobedience is time-tested and works. I haven’t been as direct, as literally present, as Jane. I wrote a series that included Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise that went up on street posters. Then I would skulk and see if anybody paid attention. The series was written from many points of view, and posed questions: What do you do with conflicting beliefs? How do you govern? How do you get along? When do you need to act, and how should you act to make things better?

JF: Particularly relevant today.

JH: Sadly. I kept on with anonymous street art, and with what might be applied art about AIDS, guns, climate, the vote. The polemical-yet-aesthetic-yet-feeling is the goal, so people might look hard, recognize, attach emotion, and move.

SH: The world is grappling with so many of these issues, and even more today. How do you respond to the deluge of obstacles we are facing?

JF: I have a moral imperative to be hopeful. If someone like me is not hopeful, what does it mean for the majority of the world that is not white and not privileged and not famous? We must be hopeful because we must continue. We have the great responsibility—and the beautiful privilege—of being alive at the moment of human civilization in which our future depends on us. That’s a fact that the scientists have been very, very clear about. We have eight years to cut our fossil fuel emissions in half. If we fail to do that, we risk going beyond the tipping points—the collapse of ecosystems of forests and oceans and air. This is a time when, no matter what else we do—whether we’re artists, painters, actors, plumbers, therapists, work at Amazon warehouses, whatever—we have to use whatever time and energy we have to do something about this. I consider the climate crisis our overarching crisis. Economically, it will cost billions of dollars to recover. Emotionally, we may not recover. Everything is challenged. Everything is thrown up in the air into utter chaos.

JH: I applaud your comprehensive statement about climate, likely the deepest human crisis. There is great lethal suffering, and there’ll be more. We’re going down if we don’t act immediately, intelligently, assiduously, and, ultimately, joyously.

JF: Everything depends on curtailing the climate crisis. There would, however, be no climate crisis if there was no racism nor misogyny. It comes out of the mentality that—how do I say this—sees humanity in a hierarchy with white men at the top and with women—especially women of color—down at the bottom.

SH: I was watching Johanna Demetraka's documentary Feminists: What Were They Thinking? Recently, in which [the artist] Judy Chicago recalls not wanting to be called a "suffragette" in the that many women today do not want to be identified as "feminist." [Director] Wendy J.N. Lee said it's something that only men do.

JH: It’s awful that “feminist” can be a pejorative. It’s stupid, counterproductive, and wrongheaded not to be a feminist. Women must have these same rights and privileges that men enjoy, for the benefit of all. Women were not born to suffer, serve, mop, be assaulted, nor killed. We tend to solve problems peacefully, and we work longer hours. What’s not to like?

JF: Feminism is not matriarchy. No, it is purely and simply about democracy. It means that all genders have equal rights, equal opportunities, and equal value to be heard. Women are very powerful, and I think that has been very frightening for people of other genders. One of the ways that men control women is by taking away their rights, including their reproductive freedoms. Keep women pregnant and that’ll curtail what they can do in their lives. The way women govern, the way women conduct friendships, the way women solve problems—all of these things are what are going to save us if anything is going to save us. The important thing to keep in mind is that feminism equals democracy. Unless you like plutocracy or autocracy, you’re a feminist. If you’re a woman or a girl and feel that you deserve equal opportunity, you’re a feminist.

SH: With all these social constraints, many women are forced to pave paths on their own, and it's an uphill battle. Jenny, you were the first woman to represent the U.S. in the Venice Biennale.

JH: Yes, I was the first American woman with a solo show. It was in 1990, and [it was] absurd that it took that long. Recently, the first woman of color represented the U.S., and that timing is absurd too. What’s significant is how much is eroding for females. “Eroding” is too passive of a word. Women are under attack. Women are denied, harmed, controlled by old-guy—mostly white-guy—policies. How reprehensible, how retro, how dopey.

JF: We’re being attacked for the way we are, because we’ve been successful in coming out from under all our oppressions. Patriarchy is like a wounded beast, and God knows wounded beasts are the most dangerous of all. We’ve been fighting back with everything we’ve had from the very beginning of time.

SH: What do you think we need from this next generation of women?

JF: I have nothing to say to young people. They’re the ones that are saying to me, “Come on, old people, fight with us, stand beside us. We didn’t create these problems. You’ve got to help us fight for our future.” I want to encourage women like me to stand up and join the movement. Level the playing field. Women are leaders.

JH: You’ve said it and lead it. Generalizing here, but women are certain about much that matters, are capable against the odds, are savvy from savage experience, are inclined to care, shield, and cure despite routine interference and provocation. Young women recognize the future, and I sense that most will not quit, that many are equal to the task—and must be. Importantly, young women feel equal.

JF: I have been gifted with privilege from the very moment I was born. Because of my family and the opportunities that I’ve had, I’ve always felt that it was incumbent upon me to use my privilege and my platform.

SH: You're quite humble to say that, Jane. There are many that have been given various privileges and haven't done the same. Jenny, was there a certain catalyst in your life that made you want to dedicate it to making people think?

JH: I come from a family full of trouble. Tragedy and malfeasance were not foreign, and it hit me early that something must, would, could, and should be done. I was never—and still am not—confident of my ability to effect change, but to live in good faith, you try.

JF: I’m so sorry that you had to endure that kind of early life, but you know what they say: God doesn’t come to us through our awards and our successes. God comes to us through our wounds and our stars. I have a feeling that’s filled with holiness.

JH: At least I had a thorough early education. Very little surprises me, but many things still delight me.

JF: Oh, that’s beautiful. Whatever else goes on, we must maintain our ability to be delighted, to be joyful, to be in awe.

JH: This goes to being hopeful enough to act.

SH: You have both been arrested a few times. Was there ever a moment that either of you considered giving up or turning the volume, so to speak, down?

JH: Jane, you’ve been arrested more than I have. I’ve been pulled into the back of police cars, but then let go. [Laughs.]

JF: In the spring of 2019, I was really depressed because I knew that the climate situation was getting worse. I turned to Green peace, and we started Fire Drill Fridays. For four months, we held rallies in front of the Capitol, and I got arrested with hundreds of other people. It caught a lot of attention, and we have recruited many new activists from all over the country. When COVID-19 hit, we started doing it virtually, and in 2020 we had 9 million viewers across all platforms. One reason that I keep doing it is because I’ve always been very aware of being Henry Fonda’s daughter or some old movie star.That when I show up, people would go, “Oh God,she’s not going to last.” But I tend to dig my heels in when you come down on me. I won’t give up. Sometimes I stop a little bit, because I have to make money. [Laughs.] But no, I don’t want to give anyone the opportunity to say, “See, she was only in it for the short haul.”

SH: Jenny, were you ever discouraged?

JH: It’s impossible to be a good enough artist. So that’s discouraging on a daily basis, but no, I’ve never wanted to quit.