Anthropomorphic sculptures made from velvet, satin and spandex—like techno-fantasy fashion objects—make up part of Florencia Escudero’s debut solo show at Kristen Lorello in New York’s Lower East Side. This collection of sculptural works is embedded with abstracted images of feminine body parts such as mascaraed eyes, dangly legs with shiny, electric-blue tights and delicately gloved hands—images Escudero gathered online from fetish sites and reworked into her own freakish, futuristic creations.

Informed by an interest in sex fetish economies, particularly the sex doll industry, and technology’s role in shaping that industry, Escudero creates her soft sculptures while thinking about the long history of the dissection of the female body in the name of science and the medical industry, and now the creation of faux body parts for fetish markets that are largely void of women. “I had the realization that these products were inspired by women but no women make money from them. It’s not like porn or sex work where at least the porn star or sex worker makes money. Here, no women make money, yet their image is exploited,” Escudero tells me.

Her sculptures on view at Kristen Lorello evoke desire and their luscious textures and curious details beg to be touched. Hung from a silver chain like a handbag or a chandelier, Reptilian Couture (2019) is a five-legged silhouette created from photoshopped images digitally printed onto satin, which the artist then silkscreens, embroiders and sews by hand. Small thorn-like growths dot the shiny sculpture, as do a layer of tattoo-like plastic drawings of flowers and butterflies created with a 3D pen. Plexi-mirror charms dangle from the mutant object’s blue toes.

In her Williamsburg studio, the books Medical Muses, Pornotopia and Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters are strewn across her desk, along with a 3D rendering of the vase-sculpture Hospital de Espejos (2019), transposed with an image of a butt. Her research surrounding gender in the realm of monsters, porn and medical experimentation on women helps situate the ideas in her series “From the Hospital to the Hotel.” “Women’s bodies have not only been pulled apart for sexual interests, but there is a history of medical experimentation on women’s bodies especially with the history of hysterics,” she tells me. More specifically, she talks of horrid historical events in which mentally ill women were tortured through their female organs. Her research into the treatment of “hysteria,” once considered an exclusively female condition, led her to Asti Hustvedt’s 2011 book Medical Muses. The book outlines a history of the medical torture that 19th century French neurologist Jean Charcot inflicted on female patients in an attempt to understand their ailments, which included the use of an instrument called the “ovary compressor.”However, what initially drove her to begin creating her sumptuous creature objects fused with images from deep-web sex sites was an interest in customizable sex dolls, artificial intelligence and what creates the desire for these products. “At a certain point you can just start buying [faux] body parts. You can buy a breast and combine it with a vagina, or feet, or legs... it becomes this thing that isn’t even a human anymore.” Engaging the idea of deformity, many of her sculptures have protrusions or growths. Every gloved arm on the six-armed figural piece Lion’s Breath (2019) grows a row of baby arms, each of which are then covered with a customized, plush teddy bear robe and paired with handmade pleather sneakers. The textural elements and the fact that every piece is handsewn gives the work a level of intimacy that makes me wonder if she believes it to be an intervention in a market lacking humanity. “In the beginning, I thought of these works functioning as images, but with time they’ve slowly become more fleshed out,” she explains.

In 2015, curious after hearing about a fetish in which men see themselves penetrating someone or something via X-ray, she bought a clear blow-up doll from China and began creating her own love dolls. Her research into these elusive transparent dolls led her to online forums where men would share photos of their sex dolls out in the real world, doing yoga or on the beach in a bikini, “reading” a book. “The photos were not always sexual, but loving. What was more interesting to me was the documentation and the desire to share the documentation.” And while the work poses serious questions about violence, gender equality and the future of desire in an age of “digisexuality” and ankle vagina fleshlights, pieces like Lions Breath and Hospital de Espejos—a smirking vase with slitted bedroom eyes, thin eyebrows and a very desirable hip to waist ratio—are also humorous. “It’s kind of like a little devil,” she says laughing. “In the work, I try to be playful because it’s a little funny. I think it’s funny when people talk to Alexa.”

She began photographing her first series of love dolls in extravagantly kitsch fantasy hotels designed for love-making. The gimmicky New Jersey venues with camouflage-themed rooms, heart-shaped bathtubs and lots of mirrors were perfect sets for her early pillow pieces, for which images of female body parts were sourced from fetish product sites. But even the existence of a “love hotel”—itself an architectural site lavishly decorated to incite romance—became influential to her body of work.

These hotels furthered her interest in exploring how design is essential to the creation of an imaginary around desire. Who makes the design choices for something like a sex doll and will those choices further negative stereotypes? “What is a Latina or ebony doll going to look like?” she asks. And now, with new technologies surrounding artificial intelligence, sex doll manufacturers are trying to make sex dolls more sentient. Suzanne Gildert, founder of AI Sanctuary, is even collaborating with sex doll manufacturers in her quest to make robot companions more human. Referencing Isabel Millar’s work on sex bots, artificial intelligence and knowledge of the self through the study of AI, Escudero says, “The person who owns a sex doll knows it’s not alive, but the doll functions as the idea of what they want to see in the world. So the question is: what creates this desire?”

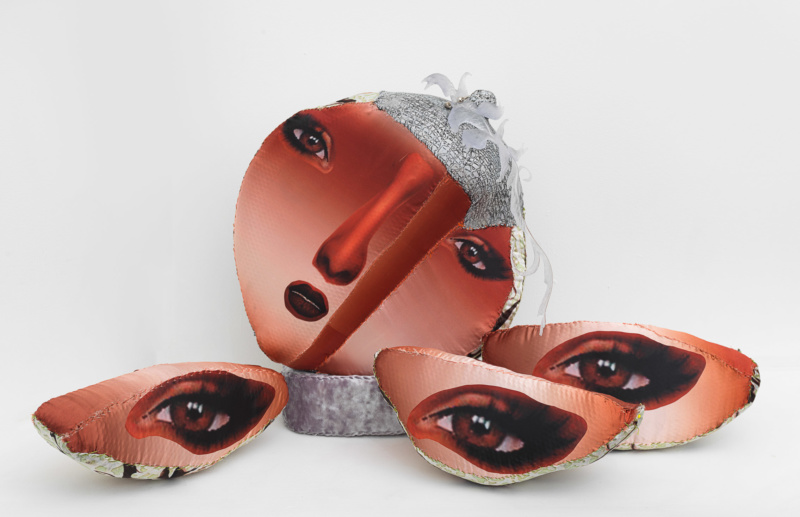

“It’s all about creating things to satisfy our needs,” she explains. “Sometimes those things are a visual marker. ‘If I have this thing I’ll be OK.’” Escudero’s sculpture Frog Licker (2019)—a round peach whose face is surrounded by peeled-off slices that peer at you with printed eyeballs—was inspired by a medieval device called the pomander, resembling an apple and divided into compartments for perfumes thought to ward off the plague. This trinket contained scents made from cloves and essential oils. Like creating a counterfeit remedy for an incurable disease, the objects we make help us build our fantasy. “The desire is for the impossible, so where does the possible fit into the trend?”

Florencia Escudero at Kristen Lorello at 195 Chrystie Street is up until January 18, 2020.