A spider isn’t taught how to spin its web, it simply knows. Like the spider, Tomm El-Saieh daubs innately, his acrylic abstractions ensnaring the eyes with their rhythmic patterns and euphonious color. Though El-Saieh finds inspiration in spiders and bee hives and other life colonies, this is not his primary muse. “I relate my paintings more to music than anything,” the artist says.

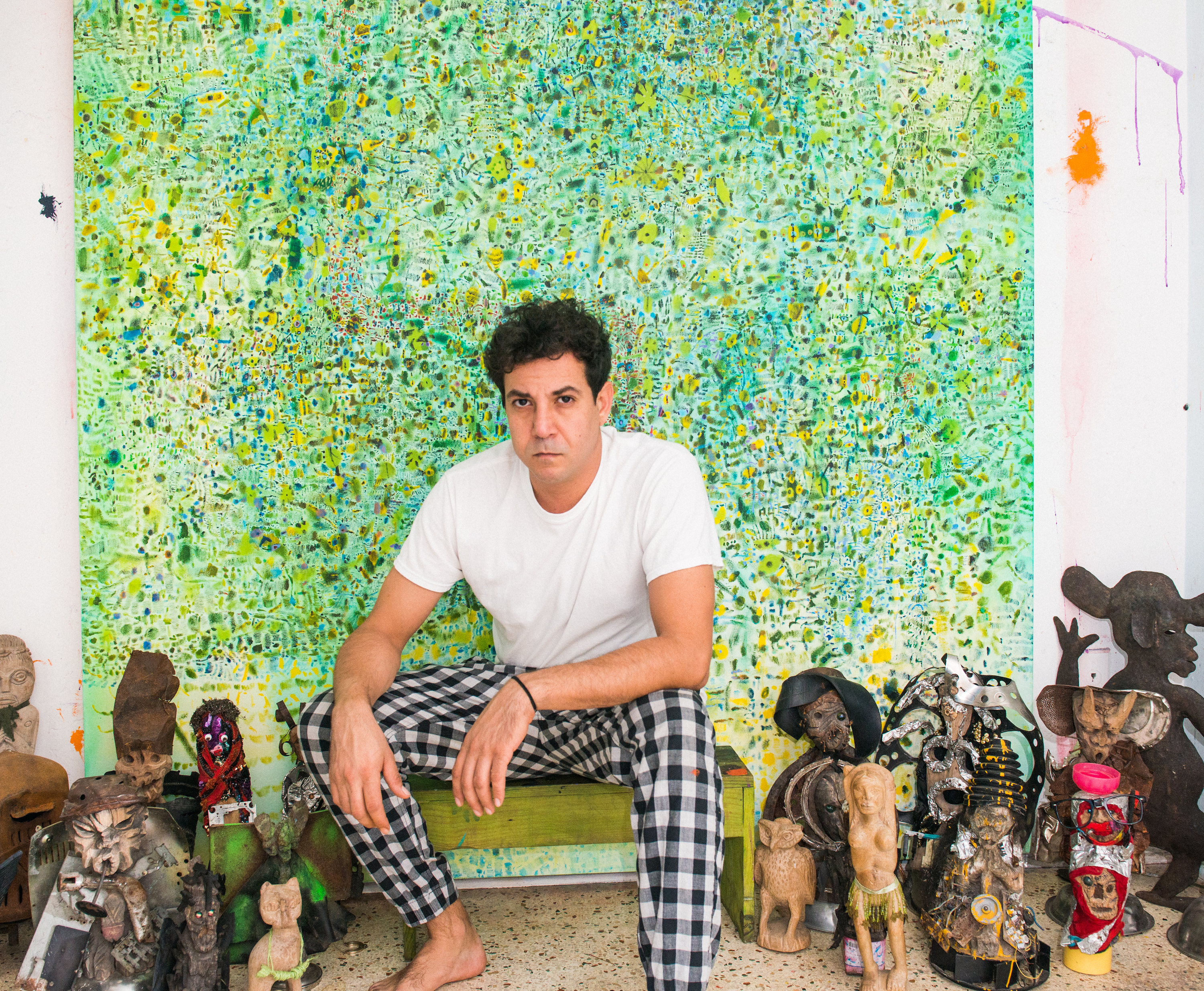

With his first solo museum show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami and inclusion in the 2018 Triennial at the New Museum in New York City, the artist has been pushing his practice to new realms. Born in Port-au- Prince and living in Miami since the age of 12, El-Saieh comes from a musical and artistic heritage that resonates strongly, but subtly, in his work. Issa El-Saieh, Tomm’s late grandfather, started his eponymous gallery in Haiti in the 1950s, where Tomm now serves as the director.

Besides molding the younger El-Saieh to enter the family business of art dealing, Issa passed on to his grandson a sense of the relationship between music and painting. Prior to opening his gallery, Issa was a maestro for a band that incorporated Vodou drumming, Cuban piano and American saxophone. “He always used the word permutation,” the artist says. “He told me, ‘It’s just a series of notes that you just move around.’”

El-Saieh’s paintings are dense with notation, shapes and scratches and swaths of color that appear to have no real-world referent. In this regard, he defies most of Haiti’s aesthetic milieu. “They always need to put the chicken in there, or it always leads to the face,” El-Saieh says of the typical work found in the Haitian art canon. “I’m removing the narrative, but it’s still the vibe of Haitian mark-making, the idea of trance.”

However, music, and the transfixing power that it can have, is key to the cosmology of Haiti. The first state to be built out of a successful slave revolt, the revolution was started with a musical Vodou ceremony. El-Saieh’s paintings don’t directly reflect this vocabulary of Vodou and music, but they remain politically-minded symphonies that hypnotize. “You go into a trance through the rhythm of drums,” El-Saieh says of his native country’s musical tradition. “It’s through rhythm, vibrations and libations.”

These rhythmic qualities, and the trance they induce in the viewer, are the most apt descriptor of the artist’s work. Undoubtedly, El-Saieh was inspired by his family and Haiti, but he also seeks to break away from the typical associations that get perpetuated about Haitian art.

“I can’t speak for Haitians or anybody really. My father’s Palestinian-Haitian, my mother’s Israeli, and I grew up here in Miami.”

And the work is clearly occupied with contemporary concerns. “His sublime, all-over compositions ask fundamental questions of abstract painting: for instance, how might painting represent subjective experience?” notes Alex Gartenfeld, one of the curators of the New Museum Triennial and chief curator at the ICA Miami. “Or further, how might an encounter with painting function today within specific traditions, whether it be 20th-century Haitian spiritualism or techno-capitalism?”

And though he finds the reference sort of dated, he cites Wassily Kandinsky’s synesthetic experience as in inspiration. The Russian artist theorized that certain colors are associated with certain sounds, which makes sense when looking at (listening to?) El-Saieh’s large, visceral paintings. They are usually bursting with color, but they’re not always oversaturated with marks and splashes.

As El-Saieh observes, “Music, I guess, is all about managing silence.”