Last week, it was announced that the 34-year-old artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby is among this year’s recipients of the famed MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship. The honor could be something of a crowning achievement following the whirlwind of recent successes that began gaining significant momentum almost exactly two years ago, when she kicked off October 2015 with a project at the Hammer Museum. The next month saw the unveiling of a Whitney-commissioned public artwork, displayed on the façade of a neighboring Meatpacking District building. The new year brought with it her first survey exhibition, which, at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, doubled as her first formal one-person museum presentation, and, in autumn of 2016, London’s esteemed Victoria Miro Gallery hosted her first solo show in Europe.

Born in Nigeria and based in Los Angeles, Crosby graduated with her MFA from Yale in 2011, culminating her academic education as an artist that she had started nearly a decade earlier as an undergraduate at Swarthmore College. Shortly after finishing at Yale, she became an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and steadily moved onto the radar of the contemporary art world in New York and beyond. Her work made its way into a number of notable group shows, like the 2015 New Museum Triennial, and “Unrealism,” the buzzy Larry Gagosian and Jeffrey Deitch-curated spectacle that took place in Miami that December. Not that she could afford to be distracted—by the end of 2015, she was looking forward to her biggest year yet.

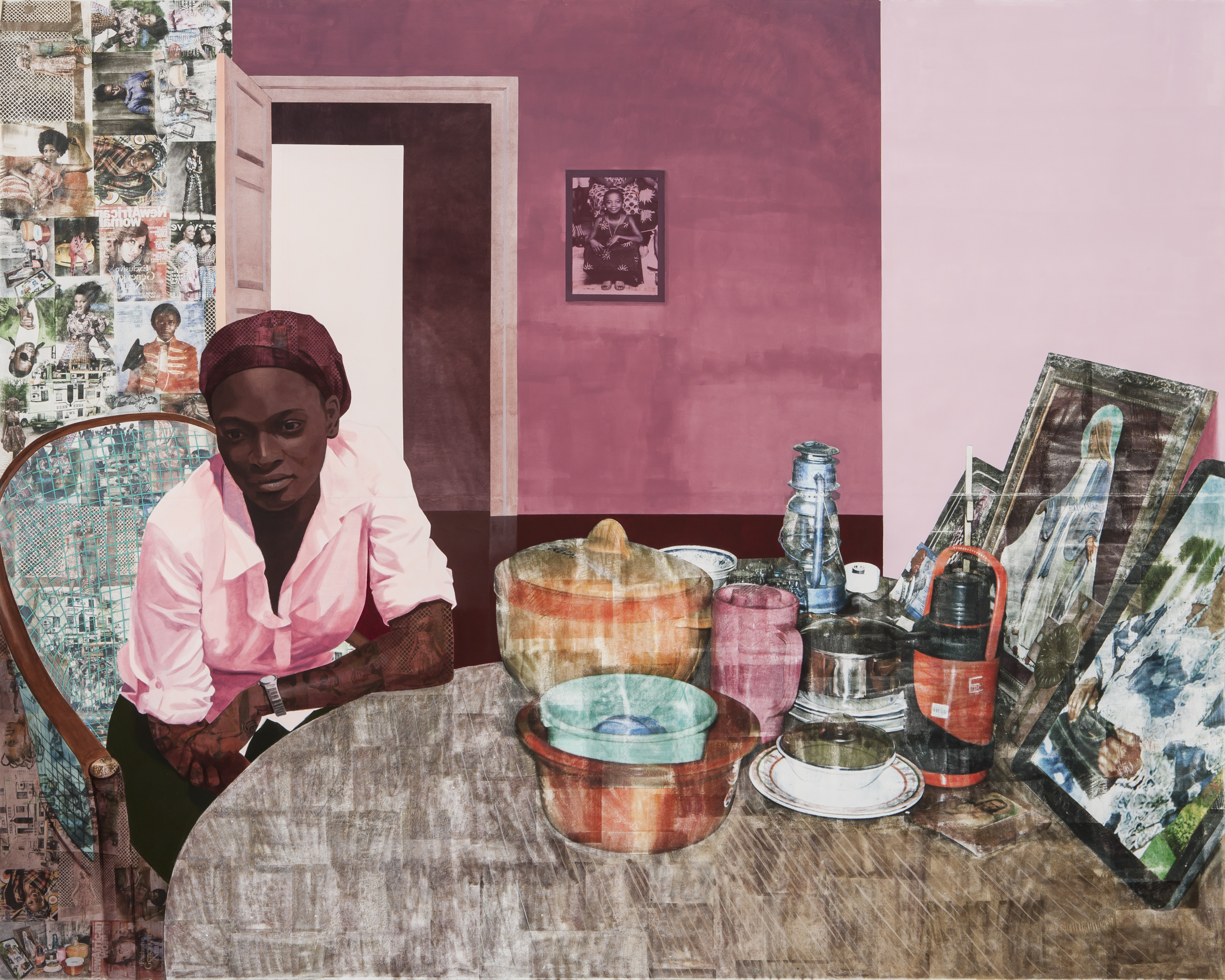

Crosby’s large-scale canvases, awash with rich colors and lively patterns, can beguile from a distance. Closer inspection will reveal enigmatic scenes, often containing one or more figures posed within spaces framed by architectural interiors that appear solid and yet feels vaguely dream-like, as if those structures had minds of their own. Physically, the works take shape through layers of paint, sketches rendered in colored pencils, graphite, or charcoal, and imagery built out using printed transfers or collage. For those who take the time to look, deeper narratives and hidden meanings will reveal themselves. “They are works that are made to be rewarding for people who come up close,” says Crosby. “I put lots of puzzles and things to entice you to come close and take a journey across the work.”

There may still be as-yet uncharted territory in the “Predecessors” series, which Crosby made between 2013 and 2016, never having had a chance to view even two simultaneously. Over the summer, all five pieces were shown together for the first time at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center. Viewed side-by-side, the portrayals of close family members—her grandmother, mother, sister, and husband—become entangled in a web of symbolism tied into her Nigerian heritage and her personal experiences as an immigrant. This past weekend, “Predecessors” debuted at the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College, where it will remain on view through the end of the year, also overlapping with an exhibition of new paintings debuting at the Baltimore Museum of Art later this month.

RACHEL SMALL: How did the “Predecessors” series emerge and take shape?

NJIDEKA AKUNYILI CROSBY: The first one, Predecessors, is where the series gets its name. When I started it in 2013, I didn’t know I wanted it to be a series. But sometimes when I start new work it's a continuation of a conversation that I had in an older work that still was unfinished. The piece that came next in the series was when I started seeing it as being connected to Predecessors. And it just kept growing—the last one was finished last year. So, I haven’t even seen two of them together in the same room! It’s out of curiosity on my part to see how they come together: works that exist as a series, not conceived of as a series. It wasn't a plan I had from the beginning.

SMALL: It’s clear that the pieces have these beautiful, tactile, well-thought-out patterns. And there are clues all around that hint at a narrative. How intentional are the narratives? Are they more open-ended, or did you have something specific in mind for each one?

CROSBY: Predecessors is a diptych. I was thinking of this split where each panel occupied a different space. The images that were used to build the composition on the right panel were mostly from my grandmother's living room in the village, and the image on the left, with the girl sitting down, was based off of photos I took that I staged in my Brooklyn apartment. All the image transfers on one side came from the generation right before mine, and all the pictures on the other side came from my generation. That was a big split for me—these two distinct spaces that I connected into one thing, where it feels like one whole world.

A year later, I wanted to revisit my grandmother's tabletop. That's when I started thinking back to Predecessors. I wanted it to be clear that I was going back to it by using this table, with all the lamps and containers and everything on it. And I used color to link the work—it's all reds and blues, varying the shades of red, going from a cold, deep, alizarin red, auburn, to a very light, hot cadmium red. So, once I got to Mama, Mummy and Mamma [2014], I went back to the tabletop and I started thinking again of these generations, the three generations of women in my family—thinking of the table as a stand-in for my grandmother, then my mother is represented in the center at the back [in an image] of her as a child, and my sister is sitting at the table. Again, thinking about generations, but doing it within one piece, whereas in the first one the panels are split.

Then came The Twain Shall Meet [2015]. I kept going back to pictures of my grandmother's table, and wanted to make a piece that was just about that. In Predecessors, it had its own panel, but it was kind of competing with the girl, and it felt like it didn’t need a figure in it to prop it up. The tabletop felt enough like a character that I could make a work of just the tabletop. I also felt like there was something alter-like about the way things were spread and stored; thinking of still-life paintings, altarpieces, I wanted to give you this feeling of orbiting around the setup, where these simple things get magnified or elevated or seem like they carry more weight than they should. I had two photographs that I’d taken of the table, one from the front and one from the back, at the same eye level. I transferred and synced them together to get one long image. The duality from Predecessors, in the diptych, was in seeing my Brooklyn apartment and my grandmother’s house in this one unified space, even though there’s space between the two. With The Twain Shall Meet, it’s seeing two different sides at the same time.

SMALL: Throughout all of the pieces, it’s hard to tell what parts derive from real-life, photographic imagery, and what elements are created from memory or from imagination.

CROSBY: There is meant to be this kind of flipping in from one to the other, where the spaces I create are unified, but you can tell something’s not coupled. For instance, in Predecessors, the girl and the chair exists [in the photograph I took], but then everything else in that panel is made up. In The Twain Shall Meet, for the table, I threw an oval in there from Photoshop [laughs]. And the background is from a [Vilhelm] Hammershøi painting.

Given this hybrid way of working, I always talk about an immigrant’s experience: you borrow or grab on to the different spaces you move through in life. At each point, you're like an amalgam of all the different places you've been and different experiences you've had and carried with you. That's how I'm composing the works.

SMALL: You’re also anticipating a show of new paintings at the Baltimore Museum of Art, titled “Front Room,” that opens in late October. What can we expect?

CROSBY: So, I'm doing a series of six works. Three compositions have mirror compositions, it's sort of a diptych; each piece has another piece that is similar to it, in that the size is the same and the compositional print is similar, but everything diverges from there. It's almost like parallel realities.

SMALL: I love how, in many of the pieces, these well-defined architectural structures ground the compositions. But often the perspective somehow seems askew, and some areas are more detailed than others, which to me suggests something imaginary and less stable, like a memory. Perhaps that effect has to do with these being multimedia works wherein the specific makeup and assembly isn’t obvious—what does your process look like in regard to the material construction?

CROSBY: It's a combination of different things. The small images are transfers, which is a printmaking technique. The objects from the table or little photographs within the work, they're printed. There are also photographs that are cut up and glued on. And then a lot of things are painted—I do a lot of washes and glazes, rolling and stenciling—and also some drawing. I’m trying to make work that samples from the different languages of image-making: I’m trying to use collage, printmaking, drawing, and painting seamlessly, and make works that reference all of those but aren’t any one of those.

For me, it’s also important in that the work is about navigating these different spaces. I grew up in Nigeria, which is a post-colonial space. Like an immigrant space, this space is where disparate cultures of people of spaces have come together. And now these spaces are very activated spaces. Nigeria is a classic example of what the post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabha describes as a space of hybridity; we used to be a British colony, there's a lot of American pop influence, there are two hundred-plus ethnic groups that are all mixed up in that, and the British and the American are giving rise to this new culture, where you can see evidence of all these influences, but what comes out of it is unique. It's not something that's static, because there’s constant appropriation. I’m fascinated at the places where we’ve taken things from—other countries, other people—and how we’re able to make it our own.

[That] ties into my making paintings: From my training at the Pennsylvania Academy, at Swarthmore College, and at Yale, all my painting training happened in the United States. How do I take the tradition I inherited here and use it to talk about Nigeria? How do I make that my own?