“How can you have an experience that feels like it opens up time a little bit?” Mira Dancy ponders, as she gears up for a late April exhibition with Chapter NY. It’s an apt query for an artist who isn’t afraid to mingle historical styles and references (Egyptian mythology, contemporary advertising aesthetics) in the pursuit of something strange and new.

Consider the 10-foot-tall painting that hangs in her Gowanus, Brooklyn studio. The work has its genesis in Jules Joseph Lefebvre’s La Vérité (“Truth”), 1870, which she first encountered at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Moved by the monumental canvas—depicting a nude female holding up a small mirror in a very Statue of Libertyesque pose—she began her own distorted riff. The artist’s truth-wielding woman flaunts mottled, multi-colored skin; a few lengths of broken chain dangle from her lowered left hand. At some point during her creative process, Dancy says, the figure seemed to want to become Melania Trump; she resisted that pull, and now any such resemblance would be glancing at best.

As a case study, this in-progress work allows for a condensed glimpse at the ways in which Dancy ingests influences—high and low, personal and topical—to advance the potentials of figurative painting. She’s as likely to draw from a historical masterpiece like Jacques-Louis David’s 1795 Psyche Abandoned as she is from a photograph of a bare-chested woman protesting a Kanye West model casting call.

Lately, like most people, she’s had politics on her mind. Another unfinished painting in the studio—this one 10 feet wide—reminds her of the dimensions of a billboard, or even a banner that could be carried at a protest march. Three distinct female figures recline against a woozy, pink-red ground; we see the words HER SEX, HER SAY floating across the surface. Small, hidden clues are

tucked away. For instance: a few wavy tendrils of foliage spell out the word Isis. (That’s a reference to the Egyptian goddess, a recurring figure in Dancy’s work, and the namesake of her 5-year-old daughter.)

So who are the women—and it’s nearly always women—who populate these paintings? Dancy envisions them all as being part of the same amorphous, evolving “campaign,” whether they’re “ancient characters, or a very day-to-day, nameless everywoman.” What they’re selling or promoting, however, isn’t always apparent, despite a recurring word— HERFUME—that sounds like a scent Calvin Klein missed out on in the late ‘90s. In fact, as Dancy makes clear, their underlying gender might not even be so cut and dry.

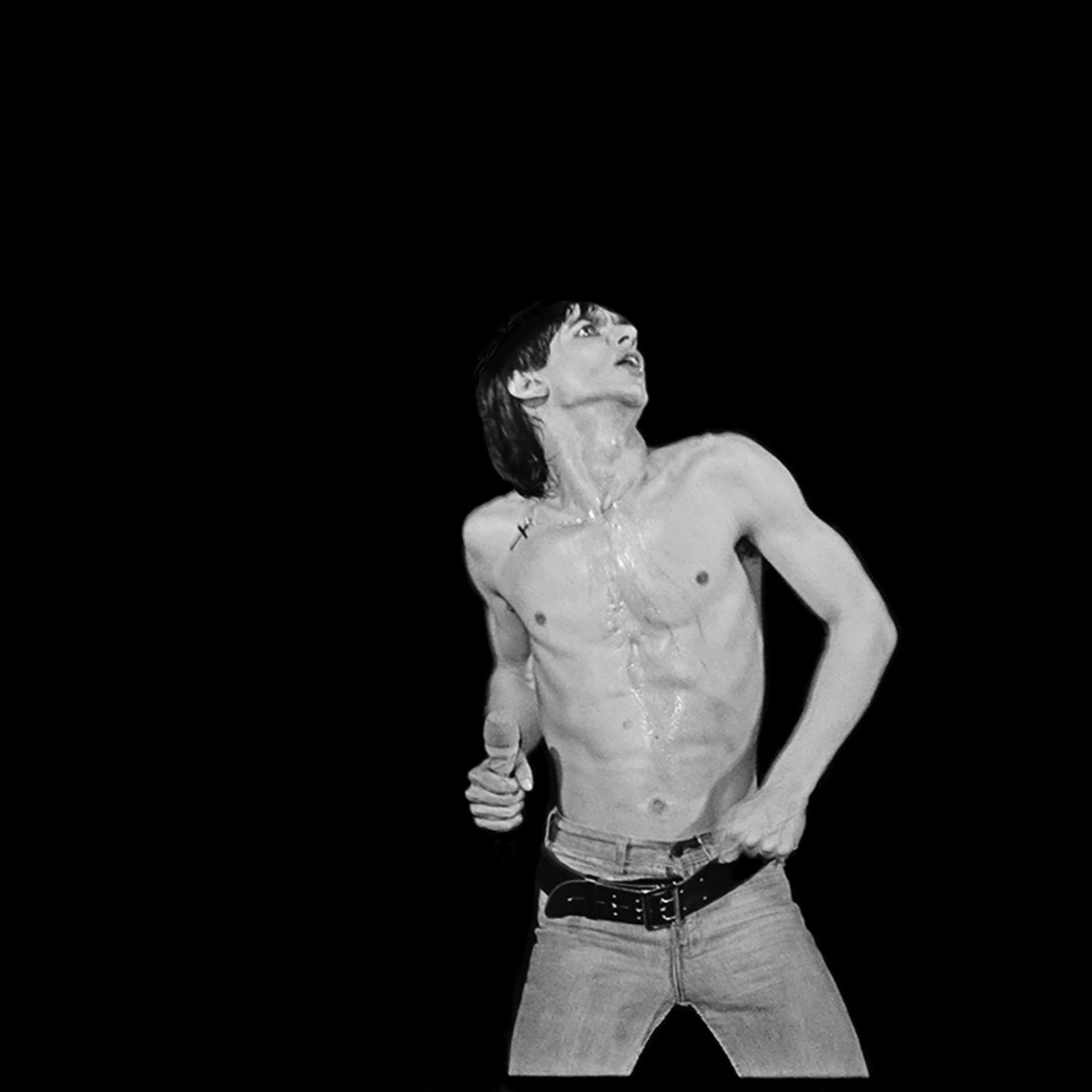

The artist was raised Catholic, and she recalls the carved wooden crucifix in the church she once attended. “I’ve been thinking that all these women I paint, underneath, maybe they’re men,” she says. “This ‘starving Jesus’ is underneath so many of the bodies.”

And sometimes Dancy’s bodies aren’t even readily recognizable as bodies at all.

At her upcoming exhibition with Chapter, which will take place across two venues—at the gallery’s main location and another Lower East Side space— Dancy plans to reveal her neon sculptures. One of the proposed pieces, which she shows me in sketch form, is meant to resemble a sort of shield or “warrior’s chestplate,” as well as a human torso cut off at the neck, or a piece of “anthropomorphic pottery.” It’s ornamented with snippets of words—YES, NOW—a reminder that for Dancy, who started out studying poetry, that painting often has its roots in language. “There’s this sense of delivery of a voice that a poem provides. I think of the paintings as picking up on that voice.”