This is Art History, your weekly primer on the art world’s salacious past. From heists to heartbreaks, CULTURED brings you the most scandalous stories from the history books, guaranteed to dazzle your dinner companions.

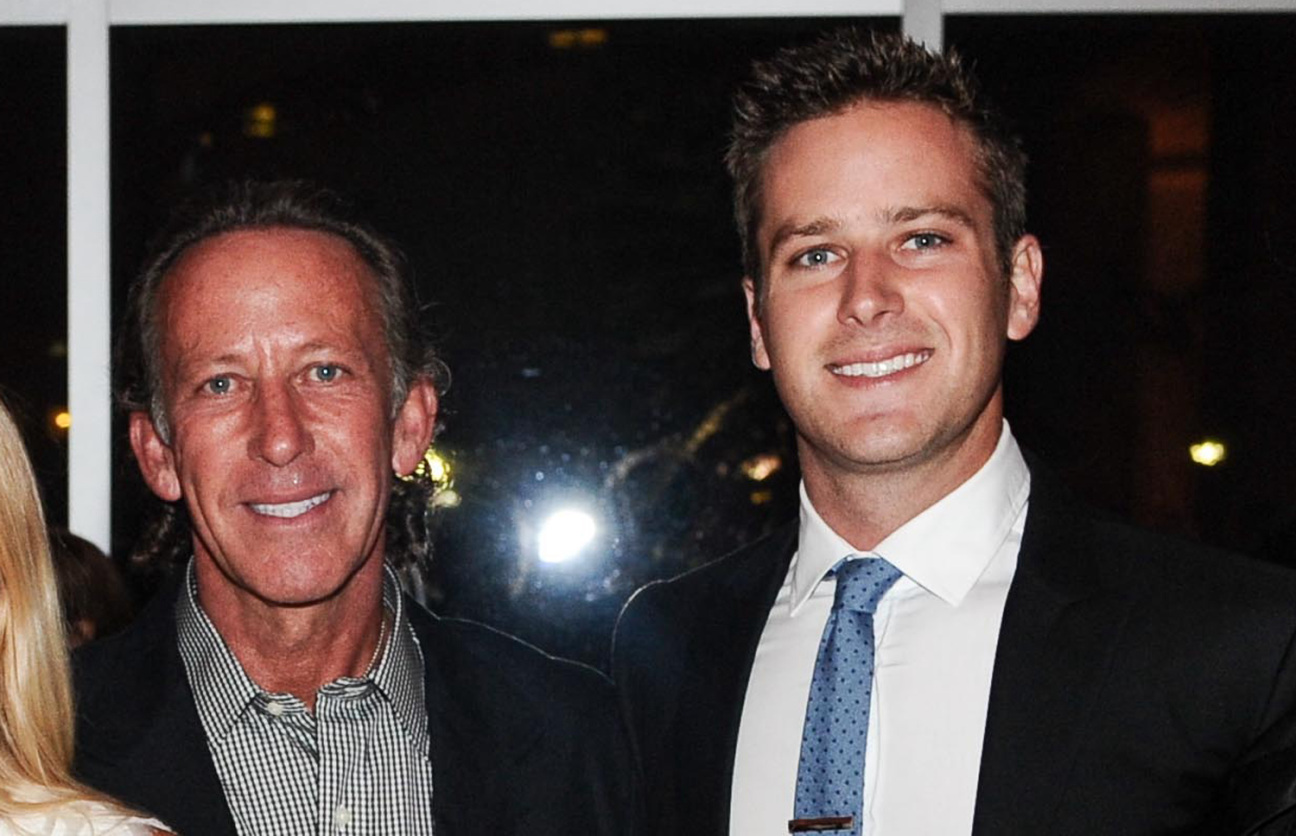

There is poetic justice in the takedown of any an old money nepo baby family, but especially when done by the hands of an unassuming math teacher from Queens. Perhaps this is why the public has responded with such glee to the ongoing breakdown of the Hammer family’s reputation. But while Armie Hammer, who was the subject of a sex abuse exposé, rife with details of cannibalistic fantasies and heavy drug use, has stolen much of recent headlines, it turns out his father has his own spiraling past.

Amidst Armie's benzo and DMT-fueled finsta posts, in 2021, Vanity Fair published an article delving into the Hammer's family history. The story characterized Michael as an immature schemer, who rode on the coattails of his grandfather, the American business tycoon Armand Hammer. Following its patriarch’s death in 1990, a bitter battle broke out between the family, a long string of mistresses, and numerous business partners to divide his $180 million fortune.

Soon thereafter, Michael set to undoing the artistic legacy that his grandfather had devoted his life to ensuring. He turned over the Hammer Museum to UCLA, and had the Metropolitan Museum of Art remove Armand’s name from the Hall of Arms and Armor, not inclined to pay off the remaining $1 million pledged. The rest of the ‘90s and early aughts include a DUI, move to the Caymans (said to be inspired by the Tom Cruise The Firm, where Michael was introduced to the tax haven), and boasting about a personalized “sex throne” that was kept at the Armand Hammer Foundation headquarters, complete with the Hammer family crest and a human-sized cage underneath its seat.

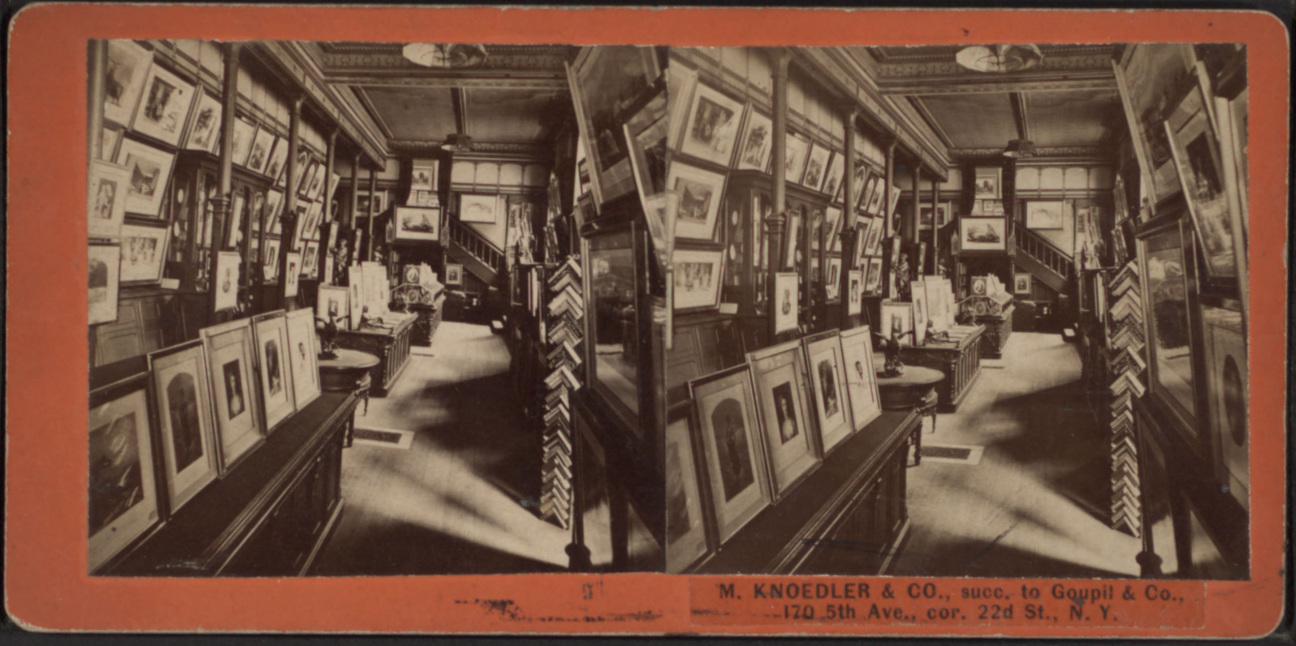

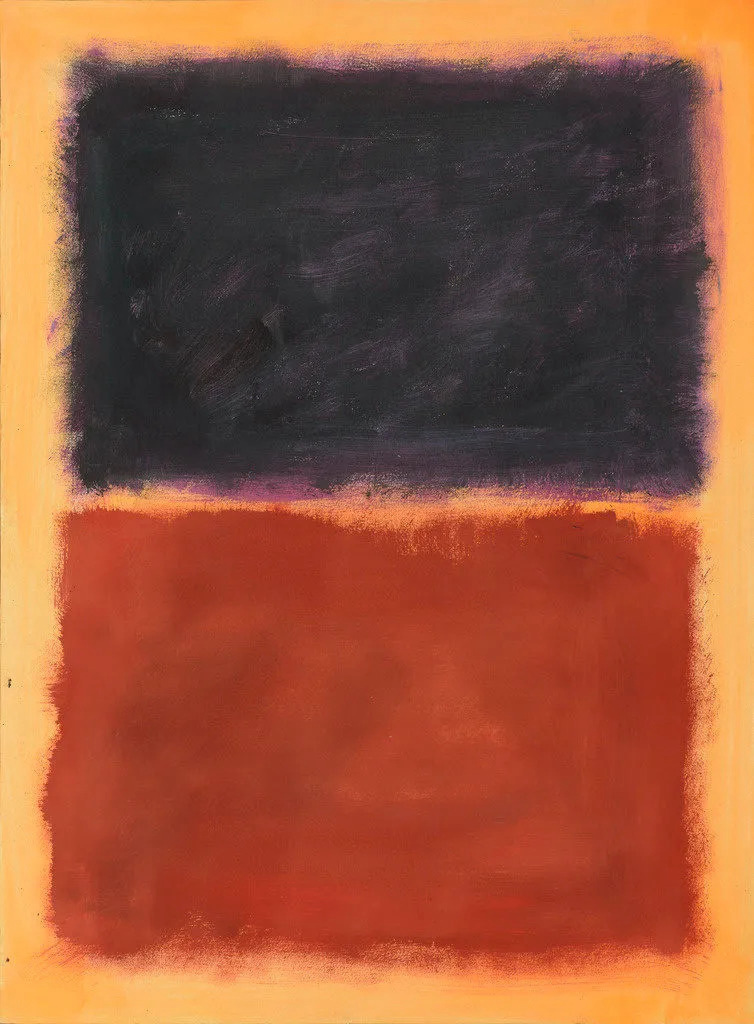

Most notable, of course, is the closing of Knoedler, a gallery bought by Armand in 1971 and one of the oldest in operation, having opened in 1846. When it finally shuttered, Michael was serving as the New York outpost’s chairman and owner. The gallery officially closed in 2011, vaguely citing it as “a business decision,” though it was obviosuly the result of selling 40 forgeries of artists including Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, and getting caught doing so. The total sum of these sales ran over $80 million.

The paintings were brought to the gallery’s director, Ann Freedman, by a woman, Glafira Rosales, claiming to be the advisor to an unnamed, wealthy private collector. In truth, Rosales was the pusher for a former math professor, Pei-Shen Qian, who was making the forgeries out of his garage in Queens. Qian started his art career in China, where he claimed that copying the masters was a common practice, rather than a scandalous taboo. Once in the states, the artist became a classmate of Ai WeiWei at the Art Students League. He sold paintings on street corners and worked in construction. Once he came into contact with Rosales, she began paying him a few hundred dollars each for his copies, eventually raising his cut as high as $7,000, despite his work going for as much as $8.5 million.

Qian denied having knowledge of the grander scheme, telling ABC News, “My intent wasn’t for my fake paintings to be sold as the real thing. They were just copies that can be put up in your home if you like it.” He points to his nominal fee as evidence. Regardless, he won’t face charges as the artist, who was 75 at the time of his indictment, now lives outside Shanghai, where he continues to paint. Rosales, on the other hand, was ordered to pay $81 million to the victims of the scheme.

Freedman was removed from her post in 2009, as the scandal began to come to light. In the Netflix documentary, Made You Look, New York Times writer M.H. Miller says, “Either she was complicit in it, or she was one of the stupidest people to have worked at an art gallery.” Despite this proclamation, Freedman did seek out experts to assess the paintings. David Anfam, a leading scholar on Rothko, co-signed the initial painting brought forward by Rosales. Still, Freeman ultimately took the fall, though she didn’t fall quite too far, going on to open her own gallery, FreedmanArt, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

In the midst of the many lawsuits filed against the gallery, all of which ended in settlements, it came out that Michael had been using the business for his own financial gain, taking money from the holdings account to purchase, among other things, two luxury cars and a trip to Paris that cost more than $1 million. Despite the nefarious dealings, Michael remained a bustling society figure until his death last year.