Guanajuato, Mexico-born and Chicago-raised artist Felipe Baeza’s Brooklyn studio is a record of his mind’s wanderings. Inspirational images from magazines and other printed matter cover the workspace walls while similar cutouts of faces, bodies, and limbs are meticulously sorted into delicate piles and shallow vessels, threatened to disarray by a breath or a sudden movement. With these disembodied parts, and a variety of other media—collage, printmaking, embroidery, painting, and sculpture—Baeza creates work that explores queer and immigrant histories, particularly the “fugitivity” of queer Brown bodies.

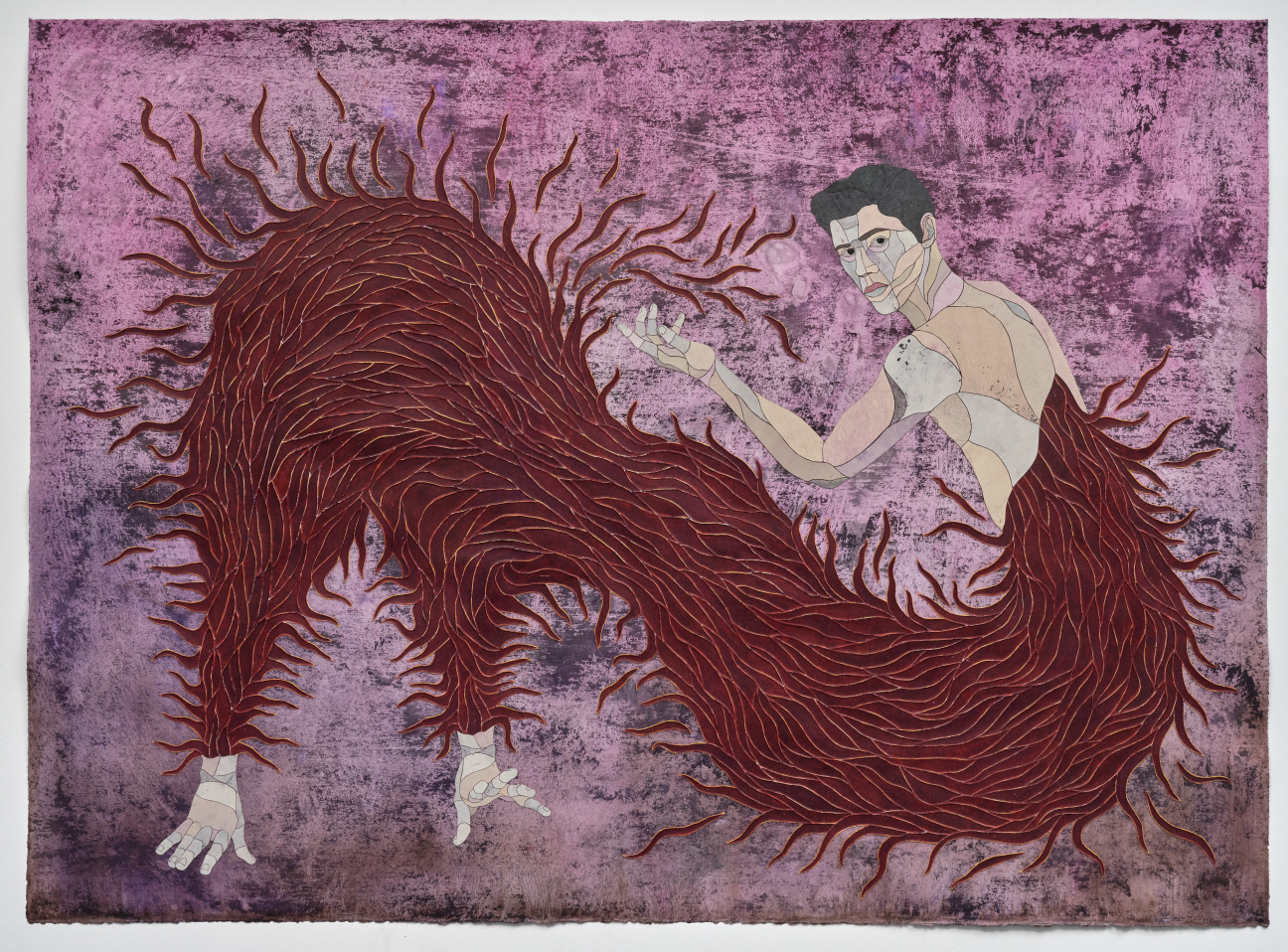

It’s a “term connected to many ways of being,” the artist revealed to The Brooklyn Rail. “The fugitive is always running and escaping, [and] it is connected to liminal and interstitial space.” In his art, this is manifested as figures of hybrid creatures, set against nondescript backgrounds on mixed mediums. In several large-scale pieces currently on view at the Venice Biennale, humanoid figures burst with foliage, both planted and uprooted. At Fortnight Institute in New York, Baeza’s second solo exhibition “Made Into Being” which is open now through October 9, the titular artwork is a centaur “made of ink, glitter, twine, graphite, acrylic and cut paper,” Yale professor Tavia Nyong’o writes in his accompanying essay, adding, “His face is a thing of beauty, a stained-glass saint for a future religion in which we are queer, post-human, and once again wild.” To Baeza, his body of work offers “room for possibility that allows a subject to live a life worth living.”

The works in the New York exhibition are a culmination of his years of sorting through one of his primary sources—“printed matter related to the classical civilization of Mesoamerica.” They are meant to set the viewer in a state of “brown study,” an archaic term, Nyong’o notes, that refers to a “moody daydream [and] a seeming stillness within which vibrant interior action is suffused.” Baeza’s artistic process, too, evokes this feeling as he constructs and reconstructs figures and their worlds, creating “new imaginaries of neither here nor there, allowing the fugitive body to make use of imagination for liberation, to transcend circumstances.”

“My work utilizes art as a tool to create political spaces,” Baeza says. “I see the body as a landscape because that’s the only landscape some of us have.”