David LaChapelle and his lens have been reimagining pop culture for more than three decades. He has documented the emergence of modern celebrity culture with unmistakable humor and wit. His two latest works "Lost + Found" and "Good News" show a photographer at the peak of his career and creativity. Cultured sat down with LaChapelle to discuss the pursuit of the transcendent, Whitney Houston and how living in Hawaii has shaped his photography.

You are releasing two books with Taschen, "Good News" and "Lost + Found," simultaneously after more than a decade. Why was the timing right now? I have always followed my intuition and it felt like the right time to complete the anthology, which started in 1996 with Hotel LaChapelle. In the past 10 years, I have been primarily focused on museum shows and exhibitions. The audience for my work has become more and more varied. It was the right time in the world to release them. I think of them as two personal exhibitions which people can own and enjoy in their own way. This has turned out to be the most intense project I have ever worked on and it is certainly the most personal project I have ever shared. I have always believed in making images that touch people.

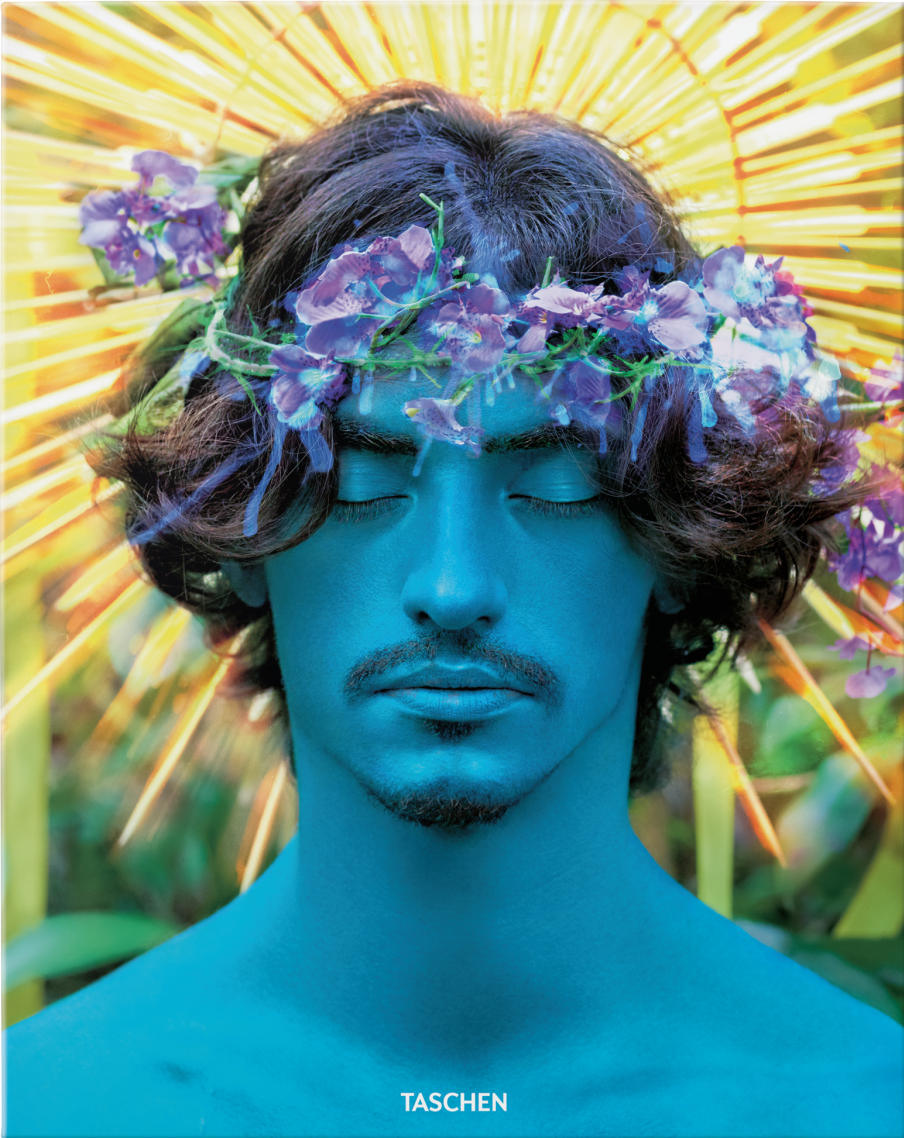

These books are the final releases of your five-book, career-spanning anthology. Did you come to any realizations of your work while curating the images for these books? Originally, I intended to just make one book. When I was laying out the images in my studio, which include work from over 30 years, I was really encouraged by the reaction of some of our younger interns. They were very excited about my very early gallery work from New York in the 1980's—which I have never published. I decided that the book needed to be in two parts, "Lost and Found," which is like a mirror of our society, and "Good News," in which I illustrate my vision of what paradise could be. I have explored visions of the apocalyptic, the utopian and the heavenly.

The books features iconic personalities as we have never seen them before, including many who have since passed. How do you feel about your role in cementing and re-imagining their legacies? This is a great question. It has been an honor of course to photograph so many artists. Music has a huge influence on my process and it has been devastating to experience the loss of many of the artists I admire. I have always tried to make the most interesting and iconic images of those I work with.

There are images of Whitney Houston in the books which I have not shown before. She was really laughing in the moment—it was so real. Whitney's good friend Robyn Crawford, who I respect greatly, and who never speaks publicly about Houston, released a simple statement where she said something like she "can't believe she will never hear her friend's laughter again."

Like in all of my work, it is important for me to represent people in a way that brings light to the world and does not bring darkness.

What are some of the most humanizing experiences that you have had with these idealized figures? I have discovered that these icons like Michael, Amy and Whitney have given the world more than they will ever receive. Artists can be very fragile by nature, and it takes a very strong person to sustain the pressure and scrutiny that comes when the entire world is watching you and expecting so much.

How do you conceive of the modern idea of "celebrities" as someone who has had personal interactions with these individuals? The photographs really answer this question. For example, the tableaux of the Kardashians, Black Friday at Mall of the Apocalypse is really about our societal obsession with this family, and is not about the family itself. You can find the answer in the pictures.

How has living in Hawaii shaped your photography? When I moved to Hawaii, I did not have a plan to make any more photographs, because I felt I had said everything I wanted to say. At the same time, museums were asking to show my work and so I returned to making images that are truly personal, without any influence from magazines or editors.

Your work “aims to photograph that which cannot be photographed.” How do you go about transcending the contradiction inherent to this goal? Pearl Lam Gallery in Shanghai is showing some of my newest series, New World, which appears in the book "Good News." The photos seemed to come to life in the gallery and almost illuminate on their own. We found out that the gallery was using a new LED lighting which can bring out the true colors from the work. It was arresting to experience this, and in the same way, many of people I have met on the book tour have described the same experience from "Good News." I was pleasantly surprised to find people are responding to work from the last 10 years, including the Paradise series, more than the celebrity work.

With over 20 years experimenting with analogue photography, I have always been interested in working in the realm of the miraculous. I am interested in the supernatural, the mystical and art which is transcendent.

Where does your work go from here now that you have completed a career-long anthology? I think the nature of an artist is to keep working, keep moving. But in the case of these books, they are like my children and I want to enjoy this moment and really be present as I see people from around the world discover them. There is nothing more important now. I don't feel the work is complete until there is a communion through art with a viewer, without words. When the time is right—I will pick up and follow my heart into the next place.